ʻAʻole mea ʻoi aku o ka waiwai e like me ke kanaka i noho kūʻokoʻa no ke aloha i kona ʻāina. 11/27/2015

ʻAʻole mea ʻoi aku o ka waiwai |

| E ka lāhui aloha ʻāina, mai Hawaiʻinuikuauli a ka mole ʻolu o Lehua, ke aloha nui iā ʻoukou. Eia nō he kupa o ka ʻāina kaulana i ke ala ʻūlili ke hoʻolono aku nei i ka leo o ke kai o Koholālele e wawā aku nei mai kahi kihi a kahi kihi o ka ʻāina kihi loa, mai ka piko o Wākea a ke kumu pali lele koaʻe. Ua ao, ua mālamalama a lohe ʻia mai ka ʻolēhala o ka leo hala ʻole o nā kai ʻewalu. ʻO kēia leo heahea, ‘o ka lāhui ʻōiwi nō ia, a ua kūpaʻa nō hoʻi i ke aloha no ko kākou ʻāina kulāiwi. Ea mai ko Hawaiʻinuiākea mai ka pō mai, puka mai i ke ao, a i lāhui aloha ʻāina kākou mai ka wā kahiko a hiki i ke au hou e neʻe nei i ko kākou kuamoʻo i hoʻopaʻa ʻia i ko kākou ʻāina. Ua nohopaʻa ua kuamoʻo aloha ʻāina nei i loko o kākou, a ua hoʻohiki paʻa ʻia i nā ʻōlelo koʻikoʻi a kekahi aloha ʻāina ʻoiaʻiʻo o Hawaiʻi, a Joseph Nāwahī, ʻo ia hoʻi “ʻAʻole mea ʻoi aku o ka waiwai e like me ke kanaka i noho kūʻokoʻa no ke aloha i kona ʻāina” (Ke Aloha Aina, July 4, 1896). Paʻa kēia ʻano o ka noho ʻana no ke aloha ʻāina ma ka moʻolelo no ʻUmi-a-Līloa, ke aliʻi kaulana o Hāmākua, ma Hawaiʻi. I ka lilo ʻana o ka ʻāina i ko ʻUmi kuaʻana, iā Hakau, a hoʻokae wale maila ʻo Hakau i kona kaikaina, hoʻi hou akula ʻo Umi mai Waipiʻo aku i ke kuamoʻo i ka ʻāina makuahine, a ua noho kūʻokoʻa ʻo ia no ke aloha i kona ʻāina. Iā ʻUmi nō e noho ʻilihune ana i ia manawa, ua lālau ʻia, pūʻili a paʻa ke aloha i ka ʻāina a lawelawe pono akula kona mau lima i ka mahiʻai a me ka lawaiʻa. Pēlā i paʻa ai ka ʻāina iā ʻUmi a kuapapa nui ke aupuni o Hawaiʻi i nei aliʻi mahiʻai a kapa ʻia he puʻipuʻi a ka lawaiʻa hoʻi. Hoʻokahua ka ʻāina, hānau ke kanaka. Hoʻokahua ke kanaka, hānau ke aliʻi. ʻO ke aloha ʻāina ke kahua, a kūkulu pono ʻia ka hālau aupuni. A pau aʻela ka hale o ke aliʻi paʻa ʻole i ke aloha no kona ʻāina. Wahi a ka poʻe kahiko, ʻaʻohe aliʻi e like me ko ʻUmi noho aupuni ʻana no kona aloha paʻa mau loa i ka ʻāina, a no kona mālama ʻana i ke kanaka nui a me ke kanaka iki. Iā ia nō i kū ai i ka moku o Hawaiʻi, ua hoʻonohopapa ʻo ia i ka poʻe akamai o ka ʻāina i kēlā ʻoihana kēia ʻoihana mai ka poʻe ʻai moku a i ka poʻe ʻai kuakua. Aia nō a nohopapa ka poʻe i ka ʻāina, kuapapa ke aupuni a paʻa ka pono o ka ʻāina no nā pua, nā mamo, a hiki i nā kawowo aloha ʻāina hope loa. He moʻolelo waiwai kēia moʻolelo no ʻUmi, e ka lāhui aloha ʻāina, i mea e ʻike ai kākou a me kā kākou mau pulapula i ka waiwai ʻoiaʻiʻo o ke aloha ʻāina. No laila, e ka lāhui kanaka, e hoʻomau aku kākou i ke kuamoʻo aloha ʻāina ʻoiaʻiʻo, e like me kā ke aliʻi kaulana ʻo ʻUmi-a-līloa. E hoʻi kākou i ka ʻāina makuahine a e noho kūʻokoʻa kākou no ke aloha i ko kākou ʻāina. Pēlā nō kākou e kūkulu hou aku ai i hālau aupuni kūʻokoʻa a pono hoʻi no kākou a no ko kākou ʻāina. ʻAʻohe mea ʻoi aku o ka waiwai Na Noʻeau Peralto Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi Nowemaba 28, 2015 | Oh nation of aloha ʻāina, from Hawaiʻinuikuauli to the taproot of Lehua, great aloha to you all. Here is a native of the ʻāina famous for the steep trails listening to the voice of the seas at Koholālele reverberating from one corner to the other corner of the ʻāina of the long corner, from the piko o Wākea to the base of the cliffs where the koaʻe birds fly. The sun has arisen, it is light, and the unmistakable, joyous sound of the voice of the eight seas is heard, and it remains steadfast in aloha for our beloved homelands. Those of Hawaiʻinuiākea rose up in the procreative night and emerged into the light. We are a nation of aloha ʻāina from the time of old until this new era moving forth because of the pathways of tradition that are fastened to our ʻāina, and these traditions are firmly sworn into the substantive words of a true aloha ʻāina of Hawaiʻi, Joseph Nāwahī, “There is nothing of greater value than Kanaka living independence through aloha for their ʻāina.” (Ke Aloha Aina, July 4, 1896) This way of living for aloha ʻāina is exemplified in the moʻolelo of ʻUmi-a-Līloa, the famous chief of Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi. When the lands of Hawaiʻi came under the control of ʻUmi’s older brother, Hakau, and Hakau continuously mistreated his younger brother with contempt, ʻUmi returned from Waipiʻo to the homelands of his mother, and there he lived independently for the aloha of his ʻāina. While ʻUmi lived in destitution during that time, he firmly grasped and held tightly to the aloha he had for the ʻāina, and with his own hands took on the work of farming and fishing. That is how the ʻāina was secured by ʻUmi, and the kingdom became unified by this farmer chief, who was also called a stalwart fisherman. The ʻāina creates the foundation upon which the people are born, and the people create the foundation upon which the chief is born. Aloha ʻāina is the foundation upon which a house of government can be properly built. And the house of the chief who is not firm in aloha for their ʻāina will be easily destroyed. According to the people of old, there was no other chief who could compare to the kingdom established by ʻUmi, because of his eternal steadfastness in aloha for the ʻāina and his care for the “big person” and the “small person.” When he became the ruler of the island of Hawaiʻi, he established in place all of the brilliant, intelligent people of the ʻāina in each and every facet of society, from those who ruled the districts to those who tended to the small, cultivated patches. It is when the people were established generationally in place that the kingdom was secured in unity, and the pono of the ʻāina was solidified for the many descendants and offspring, until the most distant progeny of aloha ʻāina. This moʻolelo for ʻUmi is a very valuable one, oh nation of aloha ʻāina, so that we, and our descendants, may come to know the true value of aloha ʻāina. Therefore, oh native nation, let us continue along the pathway and perpetuate the traditions of true aloha ʻāina, as did the famous chief ʻUmi-a-līloa. Let us return of our motherlands and live independently for the aloha of our ʻāina. That is how we shall again build an independent house of government that is pono for us and for our ʻāina. There is nothing of greater value. By Noʻeau Peralto Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi November 28, 2015 |

Eia mai kekahi mau mana o ka moʻolelo no ʻUmi (Here are some other versions of the moʻolelo for ʻUmi):

A eia hoʻi kekahi mau ʻatikala e pili ana i ka Lā Kūʻokoʻa ma Hawaiʻi nei (And here are some articles about Lā Kūʻokoʻa, Independence Day here in Hawaiʻi):

- “Ka Moolelo Hawaii,” Ke Au Okoa, Now. 3, 1870, na Samuel M. Kamakau. An English translation is provided here in Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi.

- “Ka Moolelo no Umi: Kekahi Alii Kaulana o ko Hawaii Nei Paeaina,” na Abramham Fornander.

A eia hoʻi kekahi mau ʻatikala e pili ana i ka Lā Kūʻokoʻa ma Hawaiʻi nei (And here are some articles about Lā Kūʻokoʻa, Independence Day here in Hawaiʻi):

- "A Time to Remember." Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika, Buke I, Helu 10, Aoao 2. Novemaba 28, 1861.

- "The 28th of November." Elele Hawaii, Buke 9, Pepa 19, Aoao 75. Dekemaba 1, 1854.

3 Comments

Every place has a name, and every name has a story.

Here is one short story (of many untold) for a place whose name is familiar to many, but whose history is known by few. Here is a story of a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua.

Here is one short story (of many untold) for a place whose name is familiar to many, but whose history is known by few. Here is a story of a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua.

Whether you are a diehard Tiger or an occasional passerby, and definitely if you’re a born-and-raised kamaʻāina, there’s a good chance that Paʻauilo has influenced your life in some way. No joke. “That small country town?!” You might be thinking to yourself. Yeah. It doesn’t look like much to most, but I can assure you that if you are Kanaka and/or a kamaʻāina of Hawaiʻi Island, this place—now recognized as a “town,” whose name is derived from the ahupuaʻa in which it is located—has played some sort of role in your past, present (and if not, then future) experience of Hawaiʻi. So if you’re not from Paʻauilo, or Hāmākua, then let’s begin at the most basic, surface level: Earl’s. Chances are, if you’ve driven through Hāmākua on your way to Hilo or Waimea, you’ve stopped at Paʻauilo Store and bought a bento roll made by Earl’s. If you haven’t, pua ting you. Well maybe you didn’t happen to have cash on you when you stopped, so you just took the opportunity to use the porta-potty outside the store. Either way, Paʻauilo is generally a midway stop for commuters, cruising locals, or tourists, and a central hub for kamaʻāina of the area. It’s about 40 minutes from Hilo, and about 25 minutes from Waimea. So if nothing else, at the very very least, your belly and bladder can probably thank Paʻauilo for tiding you over on your long journeys.

Okay, let’s kick it up a notch. Up until the early 1990s, Paʻauilo was smack-dab right in the middle of the island’s century-old sugar industry. Paʻauilo was a bustling plantation town made up of various “camps”—Old Camp, New Camp, Japanese Camp, Haole Camp, Nakalei—a school (home of the Paʻauilo Tigers), a store, a post office, a few churches, a ball park, and a couple generations of kamaʻāina, most of whom led humble lives shaped by sugar or cattle. A handful of my ancestors experienced Paʻauilo in this way, and developed a deep love and respect for this ʻāina, like many others. Those memories, however, remain beyond the realm of what my eyes have seen, and would best be shared by those whose eyes have. So let’s continue on this path, and talk a little more about what is unseen by most about this place.

Okay, let’s kick it up a notch. Up until the early 1990s, Paʻauilo was smack-dab right in the middle of the island’s century-old sugar industry. Paʻauilo was a bustling plantation town made up of various “camps”—Old Camp, New Camp, Japanese Camp, Haole Camp, Nakalei—a school (home of the Paʻauilo Tigers), a store, a post office, a few churches, a ball park, and a couple generations of kamaʻāina, most of whom led humble lives shaped by sugar or cattle. A handful of my ancestors experienced Paʻauilo in this way, and developed a deep love and respect for this ʻāina, like many others. Those memories, however, remain beyond the realm of what my eyes have seen, and would best be shared by those whose eyes have. So let’s continue on this path, and talk a little more about what is unseen by most about this place.

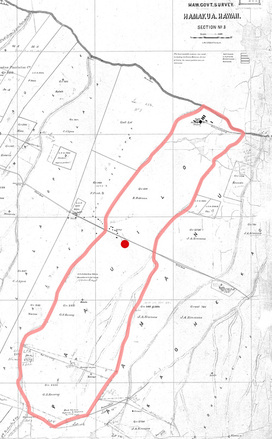

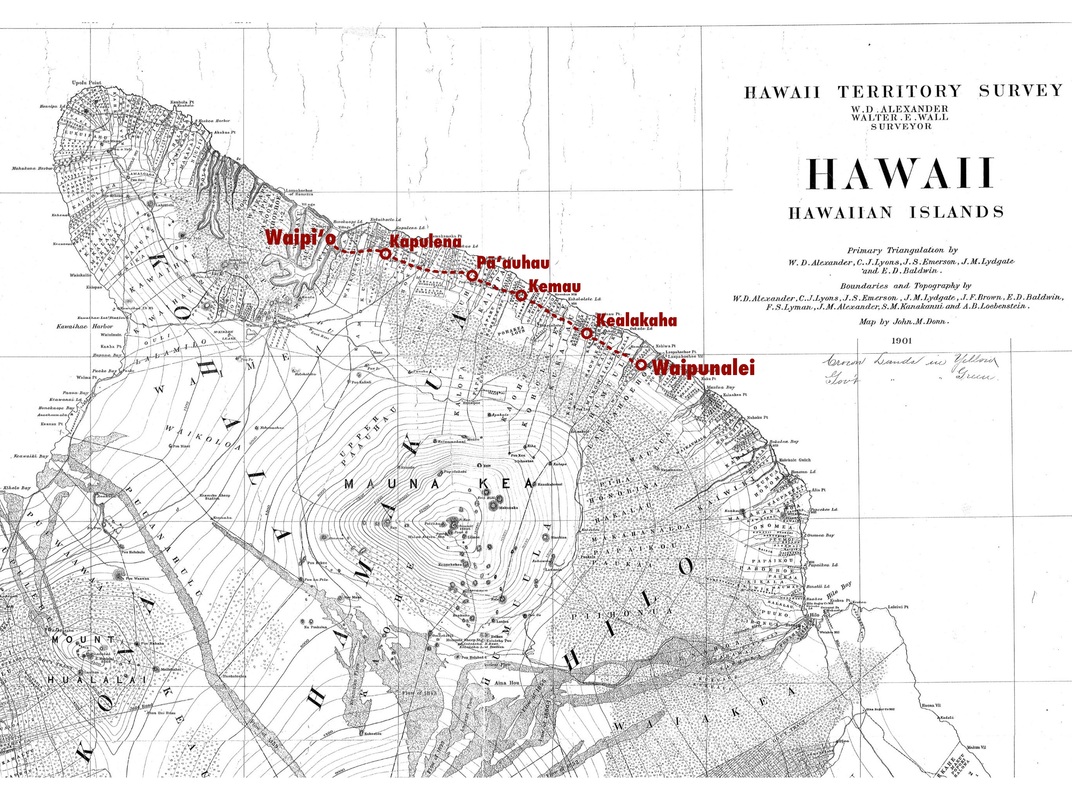

1881 Map of the Ahupuaʻa of Paʻauilo (Reg. Map 855) Red dot indicates where Paʻauilo Store is today.

1881 Map of the Ahupuaʻa of Paʻauilo (Reg. Map 855) Red dot indicates where Paʻauilo Store is today. Paʻauilo, called “Pauilo,” or something close to “Pawilo” by most people today, is one of over 130 ahupuaʻa (ancestral land divisions) located in the district of Hāmākua. In the early 1800s, this ahupuaʻa was the kuleana of an aliʻi wahine by the name of Mikahela Kekauonohi. She was a high-ranking chiefly grandchild of Kamehameha I and kiaʻāina (governor) of Kauaʻi. As part of her "payment" to the government for lands received during the Mahele of 1848, Kekauonohi relinquished Paʻauilo to Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli), who later set the ahupuaʻa aside as part of the Government Lands of the Kingdom. Not long after, George S. Kenway and Robert Robinson, two haole men, purchased most of the ʻāina in this ahupuaʻa from the Kingdom government as Royal Patent Grants 2221, 2222, and 663—“Koe naʻe ke kuleana o nā kānaka”—"Subject to the rights of native tenants." These land sales would eventually plow the way for the establishment of large-scale sugar in the area.

Prior to the Mahele, Paʻauilo, like other relatively small ahupuaʻa in Hāmākua Hikina (east Hāmākua), was likely home to about 150-200 Kānaka. Early European explorers and American missionaries described the area as fertile and highly cultivated, dissected by the multitude of streams that, now dry, once cascaded off the edge of Hāmākua’s sheer cliffs. One of these streams, Waipunalau, which forms the Kohala-side boundary of Paʻauilo (adjoining the ahupuaʻa of Paukiʻi), is fed by a spring named Waihalulu. Once favored by the kamaʻāina of Hāmākua Hikina for its “wai māpuna ʻono huʻihuʻi” (deliciously cold fresh spring water), Waihalulu was visited by Kamehameha I and his koa when they retired from the battle of Koapāpaʻa. Koapāpaʻa, located in the ahupuaʻa of Kūkaʻiau (just over a mile from Paʻauilo) was the site of the last battle fought by Kamehameha on Hawaiʻi Island in his campaign of unification. The 1791 battle began with Kamehameha holding a ceremony at Manini heiau in Koholālele, and ended with Keōua-kūʻahuʻula, the reigning chief of Kaʻū, seeking refuge under a large stone in Kainehe, which later came to bear his name: Pōhaku o Keōua. The battle proved to be a decisive victory for Kamehameha, as he soon gained control over the entire island.

Prior to the Mahele, Paʻauilo, like other relatively small ahupuaʻa in Hāmākua Hikina (east Hāmākua), was likely home to about 150-200 Kānaka. Early European explorers and American missionaries described the area as fertile and highly cultivated, dissected by the multitude of streams that, now dry, once cascaded off the edge of Hāmākua’s sheer cliffs. One of these streams, Waipunalau, which forms the Kohala-side boundary of Paʻauilo (adjoining the ahupuaʻa of Paukiʻi), is fed by a spring named Waihalulu. Once favored by the kamaʻāina of Hāmākua Hikina for its “wai māpuna ʻono huʻihuʻi” (deliciously cold fresh spring water), Waihalulu was visited by Kamehameha I and his koa when they retired from the battle of Koapāpaʻa. Koapāpaʻa, located in the ahupuaʻa of Kūkaʻiau (just over a mile from Paʻauilo) was the site of the last battle fought by Kamehameha on Hawaiʻi Island in his campaign of unification. The 1791 battle began with Kamehameha holding a ceremony at Manini heiau in Koholālele, and ended with Keōua-kūʻahuʻula, the reigning chief of Kaʻū, seeking refuge under a large stone in Kainehe, which later came to bear his name: Pōhaku o Keōua. The battle proved to be a decisive victory for Kamehameha, as he soon gained control over the entire island.

Nā pali loa o Hāmākua. Photo by Author, 2015.

Nā pali loa o Hāmākua. Photo by Author, 2015. But what was Kamehameha doing in Paʻauilo? Kamehameha was not the chief of Hāmākua. Kamehameha was from Kohala, and his primary alliances were formed with other Kohala and Kona chiefs. The aliʻi ʻai moku (district chiefs) of Hāmākua at the time that Kamehameha rose to power were Kānekoa and Kahaʻi, two chiefly brothers and uncles of Kamehameha. Both Kānekoa and Kahaʻi had actually fought against Kamehameha in the famous battle of Mokuʻōhai (in 1782, near Keʻei, Kona), defending Kīwalaʻō and his kālaiʻāina (chiefly redistribution of ʻāina). After Mokuʻōhai, Hāmākua came under the control of Keawemauhili, the highest ranking chief of the ʻĪ line alive at the time. Under his protection, Kānekoa and Kahaʻi remained until a disagreement forced them to flee the Hilo chief to go live under the Kaʻū chief, Keōua-kūʻahuʻula. The Hāmākua chiefs must have been quite independent in their thoughts and actions, because not long after settling in with Keōua, another fight ensued between the chiefs, leaving Kānekoa dead and his brother grieving.

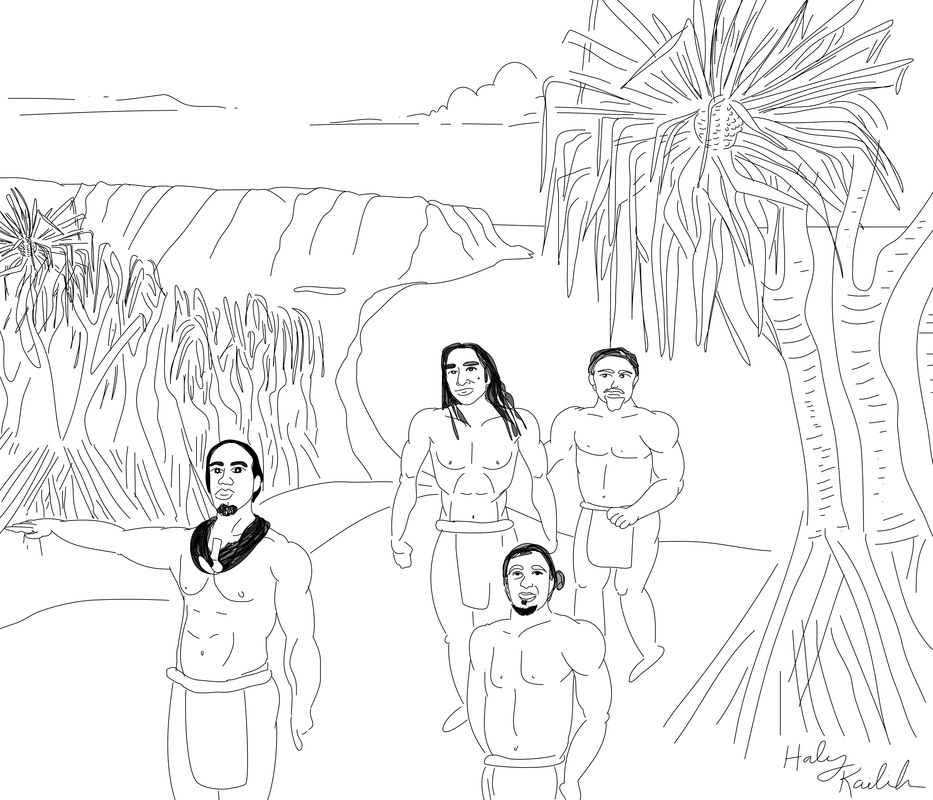

"Hā-mākua" by Haley Kailiehu, 2013. www.haleykailiehu.com

"Hā-mākua" by Haley Kailiehu, 2013. www.haleykailiehu.com During his mourning, Kahaʻi sought refuge in his nephew, Kamehameha. Kamehameha showed aloha for his uncles, recalling days when he was carried on their backs, and vowed to put an end to the Hilo and Kaʻū chiefs. It was these events, among a few others, that eventually brought the decisive battle to Hāmākua Hikina. It should be noted, however, that in his flight of defeat, Keōua was hidden and protected in Kainehe, by a kāhuna of the area, presumably with the support of the people of the area. Keōua represented the last of the ruling aliʻi of the powerful ʻĪ line that had kuleana over east Hawaiʻi (from Hāmākua to Kaʻū) since the time of ʻĪ, the great-grandson of the famous Umi-a-Liloa. The people of east Hawaiʻi were fiercely loyal to their chiefs of the house of ʻĪ, and those of the west held tightly to the Keawe clan. This battle between lineages was not a new one. It stemmed back to the generations that followed Umi’s unification of the island (about 16-17 generations before present). It seems only fitting, then, that the last battle in Kamehameha’s unification of our island would take place in the ʻāina hānau (birthplace) of ʻUmi, the great unifying ancestor from which both Keōua and Kamehameha descended. Hāmākua, then, was the "elder stalk" that held the ʻohana of moku together.

Fast forward now a few generations to another time of vast political upheaval. Following the unlawful overthrow of the beloved reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Liliʻuokalani, in Honolulu, and the onset of the United States’ prolonged occupation of our islands, Kānaka and other loyal subjects of the Kingdom fought fiercely for the restoration of our country’s independence. In addition to the organizing of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina and Hui Kālaiʻāina that effectively defeated an impending treaty of annexation forced upon Hawaiʻi by those with imperialistic interests, Kānaka leaders in the struggle for independence from both Hui also formed the Independent Home Rule Party, nā Home Rula Kūʻokoʻa. Founded in 1900 by poʻe aloha ʻāina ʻoiaʻiʻo (people truly loyal to this ʻāina), Robert Wilcox, David Kalauokalani, and James Kaulia, the Independent Home Rule Party, as their name suggests, stood for the restored independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. And their battlecry was one rooted in unification.

from Ka Naʻi Aupuni, Nov. 5, 1906

from Ka Naʻi Aupuni, Nov. 5, 1906 As part of their campaign of unification, the party published two newspapers, first Ka Naʻi Aupuni (The Conqueror), and then, Kuokoa Home Rula (Independent Home Rule). Ka Naʻi Aupuni made clear whose responsibility it was to remedy the dire situation that the lāhui had found itself in: “Na Hawaii e Hooponopono ia Hawaii,” It is Hawaiʻi / Hawaiians that will bring pono to Hawaiʻi once again. The second paper, Kuokoa Home Rula, went further to remind us of the means by which we could fulfill this responsibility. “Ma ka Lokahi ka Lahui e Loaa ai ka Ikaika.” It is in Unity that the Lāhui obtains its Strength. Without actively enacting the “hui” in "lāhui," uniting together, we would cease to exist as a lāhui, a nation.

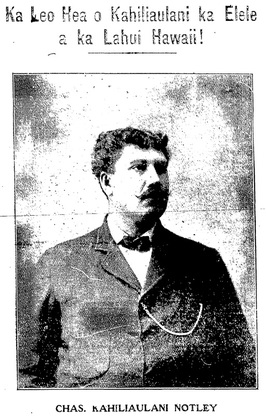

This brings us back home to the place that this story began. The owner of both papers, and later, president of the Independent Home Rule Party, Charles Kahiliaulani Notley, was a home-grown kamaʻāina of no place other than Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi. Kahiliaulani was the son of Charles Notley, Sr. and Mele Kaluahine, a chiefly descendant of Keōua-kūʻahuʻula. In 1906, while running as the Home Rule candidate for "territorial" delegate to the US congress, Kahiliaulani gave a rousing speech before supporters of Home Rule, encouraging Kānaka to unite “no ka Pono, ka Pomaikai, ka Holomua, ka Lanakila, ame ka Hanohano o ka Lahui,” for the Pono, the Prosperity, the Advancement, the Victory, and the Dignity of the Nation. In closing his speech, Kahiliaulani like many of our contemporary Kānaka leaders, likened the path ahead for the nation to that of a voyage on rough seas. As was printed in Ka Naʻi Aupuni (Nov. 5, 1906), this part of his speech went as follows:

This brings us back home to the place that this story began. The owner of both papers, and later, president of the Independent Home Rule Party, Charles Kahiliaulani Notley, was a home-grown kamaʻāina of no place other than Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi. Kahiliaulani was the son of Charles Notley, Sr. and Mele Kaluahine, a chiefly descendant of Keōua-kūʻahuʻula. In 1906, while running as the Home Rule candidate for "territorial" delegate to the US congress, Kahiliaulani gave a rousing speech before supporters of Home Rule, encouraging Kānaka to unite “no ka Pono, ka Pomaikai, ka Holomua, ka Lanakila, ame ka Hanohano o ka Lahui,” for the Pono, the Prosperity, the Advancement, the Victory, and the Dignity of the Nation. In closing his speech, Kahiliaulani like many of our contemporary Kānaka leaders, likened the path ahead for the nation to that of a voyage on rough seas. As was printed in Ka Naʻi Aupuni (Nov. 5, 1906), this part of his speech went as follows:

E hookele kakou i ke kai hoee e nee mai nei a popoʻi iho ma luna o ka lahuikanaka oiwi o Hawaii. Nolaila, i hookahi puuwai, hookahi ka manao, moe a ka umauma imua, paa like na lima i ke kaulako-waa o Halaualiiokalani, a e kahea aku au ia oukou: | Let us navigate forth into the rising seas that approach, soon to break upon our native nation of Hawaiʻi. Let us, therefore, be of one heart and one mind. Face our chests forward, and together our hands grasp and pull the canoe of Hālaualiʻiokalani. And I call out to you all: |

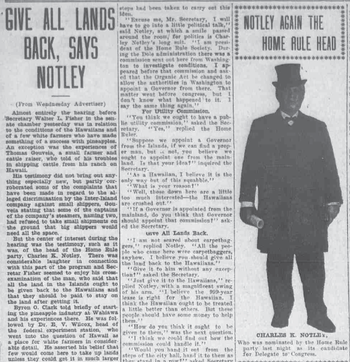

from the Hawaiian Gazette, Sept. 20, 1912.

from the Hawaiian Gazette, Sept. 20, 1912. Now a commonly heard chant at Hawaiian gatherings of all sorts, “I Kū Mau Mau” was primarily invoked to inspire collective action when pulling a large felled tree down from the uplands (such as those on the slopes of Maunakea in Hāmākua), to be carved as a canoe or heiau image. Kahiliaulani’s invocation of it in his speech may be the first recorded usage of it in the context of contemporary Hawaiian politics. Though never successful in his campaigns to become a delegate to the U.S. congress, Kahiliaulani remained a fervently loyal Home Rula and Aloha ʻĀina, encouraging our people to “pull together” until the end. In fact, in a 1912 hearing regarding the conditions of Native Hawaiians, Kahiliaulani was quoted as having testified before then U.S. Secretary of the Department of Interior, Walter L. Fisher, that the U.S. should “give all the lands back to the Hawaiians.” According to the reporter from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, many of those present in the room chuckled at what seemed to be an unrealistic proposition. But Kahiliaulani did not waver in his conviction. Not only should all the lands be returned to Hawaiians, he insisted, but the government should also appropriate sufficient funds to support Hawaiians living and remaining on those lands. Imagine that. And just a little over a hundred years later, the U.S. Dept. of Interior is still getting an earful from the brilliant aloha ʻāina of this place.

Surely Kahiliaulani is not the only historical figure from this unassuming place who deserves our praise and remembrance. He is but one of many who has been selectively honored in this moʻolelo—a moʻolelo which serves, really, to honor this place. After all, they are one and the same. And as is the responsibility of any storyteller, I will now conclude this moʻolelo where it began: in a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua. So the next time you pass by or stop at Paʻauilo Store, look ma kai across the street, and imagine Kahiliaulani once living there. And then look towards Hilo, and imagine the abundant days of Umi-a-Liloa’s youth or the awesome scene of over 30,000 koa converging in battle at Koapāpaʻa. Then look ma uka, and see the sacred summit of Mauna a Wākea, the highest peak in all of Oceania. Then look towards Kohala, towards the sacred valleys of Waipiʻo and Waimanu where generations of our most powerful chiefs once ruled. And remember why this place is called Hāmākua, "the parent stalk" of this island. And back here in the middle of it all you will find yourself, in a quiet, old plantation town, in Paʻauilo.

(Aole i pau)

Na Noʻeau Peralto

Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi

Oct. 14, 2015

Surely Kahiliaulani is not the only historical figure from this unassuming place who deserves our praise and remembrance. He is but one of many who has been selectively honored in this moʻolelo—a moʻolelo which serves, really, to honor this place. After all, they are one and the same. And as is the responsibility of any storyteller, I will now conclude this moʻolelo where it began: in a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua. So the next time you pass by or stop at Paʻauilo Store, look ma kai across the street, and imagine Kahiliaulani once living there. And then look towards Hilo, and imagine the abundant days of Umi-a-Liloa’s youth or the awesome scene of over 30,000 koa converging in battle at Koapāpaʻa. Then look ma uka, and see the sacred summit of Mauna a Wākea, the highest peak in all of Oceania. Then look towards Kohala, towards the sacred valleys of Waipiʻo and Waimanu where generations of our most powerful chiefs once ruled. And remember why this place is called Hāmākua, "the parent stalk" of this island. And back here in the middle of it all you will find yourself, in a quiet, old plantation town, in Paʻauilo.

(Aole i pau)

Na Noʻeau Peralto

Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi

Oct. 14, 2015

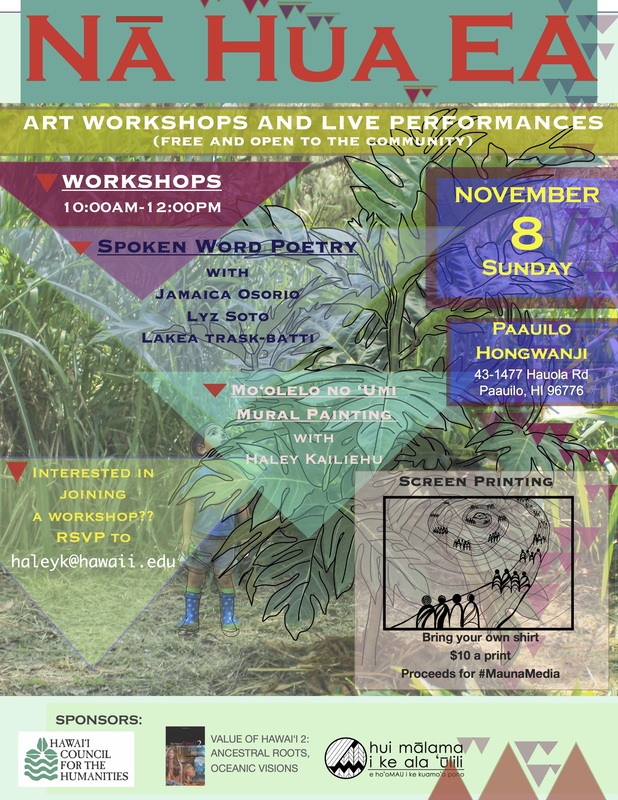

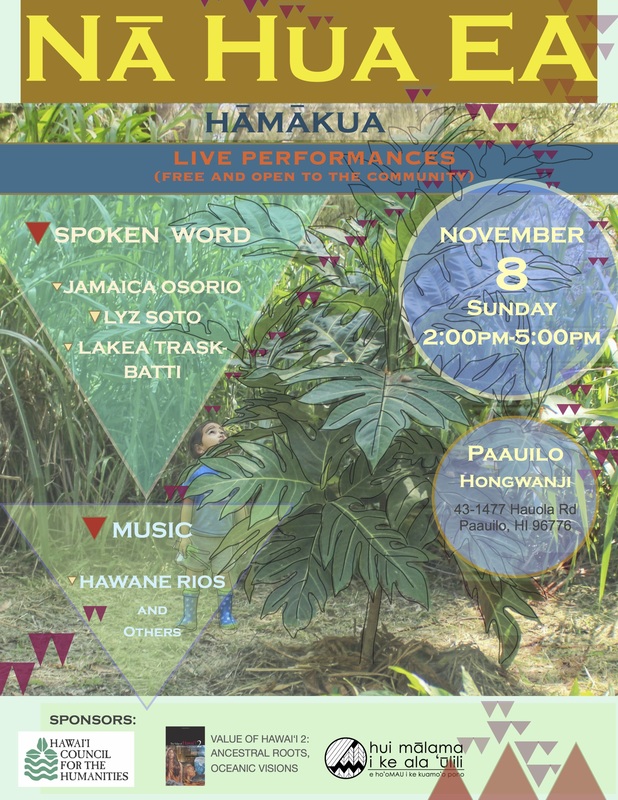

In the same spirit of unification, Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili invites all in our community to join us for Nā Hua Ea on November 8, 2015 in Paʻauilo at the Paʻauilo Hongwanji. Nā Hua Ea is an art and poetry event collaboration between the editors of The Value of Hawaii 2, the Hawaii Council for the Humanities, and huiMAU, to bring together our community to create and share art and poetry that expresses our vision of Ea, genuine life, sovereignty, and well being. The day will begin with poetry and art workshops, open to the community, and culminates with an open mic performance. Please feel free to share the event flyers below. Mahalo!

Can’t You See Us Rising?

a Blog Post by Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua

A beautifully composed "open letter to Hawaiian elders who have urged Kānaka Maoli to participate in the recent state-initiated process to establish a Native Hawaiian Roll and, what Act 195 calls, a 'reorganized governing entity,'" including some reflections from the experiences Dr. Goodyear-Kaʻōpua and her ʻohana had on a huakaʻi to Koholālele, Hāmākua in May 2015.

Read more awesome blog posts like this on the Ke Kaupu Hehi Ale Blog Page.

Read more awesome blog posts like this on the Ke Kaupu Hehi Ale Blog Page.

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

Auhea oukou e na hoa hele o ke ala ulili. E ka lahui Kanaka, mai kahi kihi a kahi kihi o ka ʻāina. Aloha nui kakou. Oiai makou e hoomanao ana i ka La Hoihoi Ea o ko kakou Aupuni Hawaii aloha, he kupono no hoi ko kakou nana hou ana aku i ke kumu manao o ia me he ea. I ka M.H. 1871 haiolelo maila o Davida K. Kahalemaile no ka La Hoihoi Ea, a he palima kona manao no ke ea. Wahi ana, "1. Ke ea o na i-a, he wai. 2. Ke ea o ke kanaka, he makani. 3. O ke ea o ka honua, he kanaka, koe nae na mea ola lua, ola i ka wai, ola i ka aina. 4. Ke ea o ka moku, he hoeuli, ka hoeuli o ke kanaka nana e pailata kona noonoo, oia ka uhane. 5. Ke ea o ko Hawaii Pae Aina, nona keia la a kakou e olelo nei a e olioli nei. Oia no ka Noho Aupuni ana. A o ke ano hoi o ka huaolelo aupuni, Oia ka hui ana o na Alii a me na Makaainana e noonoo a e kau i Kanawai no lakou, a kapa ia mai keia hui ana, he Aupuni." (Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, Aug. 12, 1871) Nolaila, e ka lahui Kanaka, ia kakou e hea aku nei i na olelo kaulana a Kauikeaouli (KIII) i i aku ai i ka La Hoihoi Ea mua loa i ka M.H. 1843, oia no, "Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono," e hoomanao no kakou i keia mau manao no ke kumu pono o ke ea. He kumu ola ke ea, a he kahua no ia no ka pono o ka aina a me ke kanaka. A ia kakou, e na hoa hele o ke ala ulili, e hahai aku nei i ke kuamoo o ke alii kaulana nona keia moolelo, e nana pono kakou i kana mau hana e kukulu iho ai i ke ea o ko Hawaii Nei Pae Aina, i kona hui ana me na Makaainana e noonoo a e hoopaa i na kanawai a i na pono no ko kakou aina aloha. | Dear traveling companions of the ala ʻūlili, oh lāhui Kanaka, from one corner to the other corner of this ʻāina, great aloha to you all. As we are now commemorating the Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea (the day that sovereignty was returned) of our beloved Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, it is absolutely necessary that we look to the source of the meaning of this thing called "ea." In the year 1871, Davida K. Kahalemaile gave a speech about Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, and fivefold were his thoughts about ea. According to him, "1. The ea of fish is water. 2. The ea of people is the wind (air). 3. The ea of the earth is people, other than the two things that give life: life from the water, life from the ʻāina. 4. The ea of a boat is the rudder. The rudder of a person which pilots their thoughts, is the spirit. 5. The ea of these Hawaiian islands, that for which this day we speak of and celebrate, is our continued existence as an independent nation. And the nature of the word aupuni, refers to the unification of the chiefs and the common people to think of and enact a set of laws for themselves. This unification is called an Aupuni." Therefore, oh lāhui Kanaka, as we call out the famous words that Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) spoke at the very first Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea in 1843, "Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono," we should remember these thoughts regarding the true source of ea. Ea is a source of life, and it is a foundation for the pono of the ʻāina and the people. And as we, oh traveling companions of the steep trails, are following in the path of the famous aliʻi for whom this moʻolelo was written, we must thoroughly look at his work to establish the ea of our Hawaiian Islands, as he united with the common people to devise and solidify the laws and the necessities of well-being for our beloved homelands. |

Helu 4 (Hoʻomau ʻia)I ka pau ana o na kanaka i kuahiwi me Kaleioku. Malamalama loa ae la, koe o Umi me na wahine ana. Puka ae la ka la a mehana, o ka hora 8 paha ia, o ka la Poaono [a ko laua huakai mai Waipio aku], a ua mau wahi elemakule nei i hiki ai i kahi o Kaleioku, me kana Alii me Umi. Hiki ua mau wahi elemakule nei, he mehameha wale no na hale o Kaleioku ma, aole maaloalo kanaka iki mawaho, kahea ae la ua mau wahi elemakule nei, "Mehameha nae na hale o ua o Kaleioku, aole maaloalo kanaka iki." Lohe ae la o Umi i keia leo mawaho, e noho ana ia ma ka hale o mua, he mea mau ia i na kahuna o ka wa kahiko, ma ka hale o mua wale no e kipa ai, aole ma ka hale moe. Kahea aku o Umi i ua mau wahi kanaka elemakule nei, "E komo olua maloko nei, aole he kanaka o ko makou wahi nei. Ua pau aku nei o Kaleioku me na kanaka i ka mahiai i kuahiwi, owau wale iho nei no koe. I hoonohoia iho nei au i kanaka no olua e hiki mai ai." Komo aku la ua mau wahi elemakule nei iloko o ka hale o mua. A puka aku la o Umi iwaho, a hopu aku la i ka pauku wahie i hoomakaukau mua ia. Hapai ae la ia a kiekie iluna, a hahau iho la ia i lalo, i ka ili o ka honua. Naha liilii ae la ka pauku wahie, ho-a ae la ia i ke ahi, a a ke ahi, no ka nui o ka pulupulu i hoomakaukau mua ia. Nui ae la ka uwahi, aole i kauia ka wahie, ua nalo nae ia i ka maka o na wahi elemakule. Hopu aku la o Umi i ka puaa, alala iho la ka puaa, hookuuia'ku no, aole i make. Ma kahi i nalo i ka uwahi, malaila kahi i hookuuia'ku ai ua puaa la. A pau ka a ana o ka opala i hanaia'i i pulupulu, kalua wale iho no keia, o kauewewe wale no, kii aku la keia a ka pu awa, a huhuki ae la, a hemo. I iho la ua mau wahi elemakule nei, kekahi me kekahi, "Ina me neia ka hanai a ua o Kaleioku, ola na iwi, kai ke kanaka ikaika." No ko laua nei ike ana i ka naha liilii o ka pauku wahie, i ka hikiwawe o ke kalua ana o ka puaa, i ka hemo ana o ka pu awa nui i ka uhuki ana. Oia ke kumu o ko laua mahalo ana he kanaka ikaika. Ia Umi i huhuki ai i ka pu awa, hoi ae la ia ma kekahi aoao o ka hale a laua nei e noho ana, (oia ka hale o mua.) Hana o Umi, wawahi a liilii ka awa, kukulu ke kanoa, a waiho iho la ia i ka awa i wali mua i ka mamaia, iloko o ke kanoa. Kii aku la o Umi i ka puaa i kalua mua ia, ma kahi kokoke i ka imu a ia nei i kalua ai, aole puaa. Huai ae la o Umi a lawe mai imua o ua mau wahi elemakule nei, ua moa lea loa ka puaa. Ia ia nei no e huai ana i ka imu puaa, olelo aku la o Nunu, kekahi elemakule ia Kamai [o Kakohe paha], "Ea! hikiwawe ka moa o ka puaa, o ke kalua ana aku nei no la?" Ae mai la o Kamai; aka, i ka hiki ana imua o ko laua mau maka, ua moa lea loa ka puaa. Hana iho la o Umi i ka puaa, a waiho i ke pa, kii aku la o Umi i ka awa a ninini iho la iloko o na apu elua. Haawi aku la o Umi no ua mau wahi elemakule nei, a inu ae la laua, paina laua a ona i ka awa, hina aku la kekahi ma ka paia, a o kekahi hoi, hina ma kahi moe. Hapai ae la o Umi i kekahi elemakule a hoomoeia'ku ma ka moe. | Chapter 4. (Contʻd)When everyone had gone to the uplands with Kaleiokū, the bright light of day emerged, and ʻUmi was left with his wahine. The sun rose and brought warmth. It was perhaps 8 o'clock in the morning, on the sixth night [of their journey from Waipiʻo] that those two old men arrived at the place of Kaleiokū and his aliʻi, ʻUmi. When the old men arrived, the houses of Kaleiokū and the others were silent. Not one person passed by them outside. The old men called out, "The houses of Kaleiokū are silent. Not one person passes by." ʻUmi heard this voice outside, while sitting inside the hale o mua (men's eating house). It was a common thing for the kahuna of the old times to only visit at the hale o mua, not at the sleeping house. ʻUmi called out to those old men, "Come, you two, inside here. There is no one else here. Kaleiokū and all the others have gone into the uplands to farm. I am the only one who remains. I have been placed here to attend to you both upon your arrival." The two old men then entered the hale o mua. ʻUmi then went outside and grabbed the bundle of firewood that had been prepared. It was lifted and held high up, then thrown down on to the ground. The firewood was broken into small pieces. The fire was lit, and it burned well, because of all the tinder and kindling that had been prepared beforehand. The smoke was huge, and no firewood remained. It all disappeared right before the old men's eyes. ʻUmi then grabbed the pig, and the pig squealed, so he released it, for it was not dead. Where it would concealed by the smoke, that is where the pig was released. When all the kindling and tinder had burned, this is what was cooked in the imu: just the ti leaf covering. He then fetched the ʻawa root, pulling it out and separating it. The old men then proclaimed to each other, "If this here is how the hānai of Kaleiokū is, the bones will live, indeed, by this strong man!" Because they had seen the bundle of firewood broken into small pieces, the quickness with which the pig was kālua, and the uprooting of the ʻawa. That is the reason for their praising him as a strong man. When ʻUmi had pulled up the ʻawa, he returned to the other side of the house in which they were sitting, (that is, the hale o mua.) ʻUmi went to work, breaking the ʻawa into small pieces, setting up the kānoa, and placing the ʻawa that had previously been softened by chewing inside of the kānoa. ʻUmi then fetched the pig that had already been kālua at a place nearby the imu in which he had placed no pig to kālua. ʻUmi uncovered it and brought it before those two old men. The pig was cooked very well. While he was uncovering the imu with the pig in it, Nunu, one of the old men, said to Kamai [Kakohe perhaps], "Wow! How quick the pig was cooked! Was it actually kālua?" Kamai nodded in agreement; but when it arrived before their own eyes, the pig was indeed cooked very well. ʻUmi prepared the pig, and placed it on a platter. ʻUmi then fetched the ʻawa and poured it into two ʻapu (coconut shell cups). ʻUmi gave them to the old men, and they drank. The two of them feasted until they were dizzy from the ʻawa. One of them laid down against the wall, and the other laid down on a mat so ʻUmi lifted the old man and laid him down on the mat as well. |

| Pii aku la o Umi iuka o kuahiwi, ma kahi a Kaleioku ma e mahiai ana me na kanaka. A loaa aku o Kaleioku ma e mahiai ana me na kanaka o laua, ninau mai o Kaleioku ia Umi, "Ua hiki mai ua mau wahi elemakule nei? " Ae aku o Umi. "Ae, ua hiki mai laua, o na mea au i ao mai ai ia'u e hoomakaukau no ko laua hiki ana mai, oia na mea ai, ua hoomakaukau aku nei no au, a ua pau. Ua ona nae ua mau wahi elemakule la i ka awa, ke hiamoe la." Olelo aku o Kaleioku ia Umi, "E noho kaua me na kanaka ou, a aui ae ka la, hoi kaua, penei nae ka hoi ana. Owau ka makamua o na kanaka, a o oe e ke Alii ka hope loa." Ua oluolu ia i ko Umi mau maka. O ka Kaleioku mea i hana ai no ka hoi lalani ana o na kanaka o ke Alii. I hiki ia mamua i na wahi elemakule, loaa ka hoa kamailio o laua. No ka ninaninau o ua mau wahi elemakule nei ia Kaleioku ia Umi. A na Kaleioku e wehewehe aku imua o laua, o kuhihewa laua i keia kanaka, kela kanaka o Umi ; no ka mea, o Kaleioku, ua kamaaina ia i ko laua mau maka. Aole no i ike laua ia Umi, a poeleele loa i ka hoi ana mai mai kuahiwi. Oia ka mea i lilo ai ka Mokupuni o Hawaii ia Umi, no ko laua hilahila ana. I ko Umi pii ana iuka, e huli ia Kaleioku ma, moe iho la ua mau wahi elemakule nei, a mahope iho, ala ae la ka lua o ka elemakule, a kamailio laua ia laua iho. I iho la laua, "Aole me keia ko kaua mau haku o ka noho ana, ia Liloa, a hala ia i ka make, ia Hakau hoi i kana keiki, he ai, he i-a, he kapa, ka mea loaa mai ia kaua, o ko kaua wahi hale pelapela loa, he oi keia a kaua e ike nei. Mai ko kaua wa u-i, a hiki i ko kaua wa hapauea nei, loaa ia kaua keia mau makana maikai, i ko kaua wa ahona iki, aole i loaa." A aui ae la ka la, o ka hora 2 paha ia, hoomaka ka iho ana o ka huakai, o Kaleioku mua, ia lakou nei e iho mai ana. Ike aku la ua mau elemakule la i ka iho ana mai, aia hoi, ua nui loa na kanaka imua o ko laua mau maka, i ka ike aku e iho mai ana, aole nae i ikeia'ku ka hope pau mai o na kanaka, i ka puka ana mai maloko o ka laau loloa. Ma kela aina, i haiia ma ka Helu 2 o keia moolelo, (o Waipunalei ma Hilo paliku.) A hiki o Kaleioku imua o ke alo o ua mau wahi elemakule nei, aloha lakou ia lakou iho, akahi no lakou a halawai hou, ua nui loa ko lakou aloha ia lakou. Ke hoi nei no na kanaka ma ko lakou mau hale, e kokoke ana ma ko lakou nei hale e noho ana, (oia ka hale o mua,) o kanaka nui wale no keia e e hiki e nei i kauhale. Ua mahele o Kaleioku i na kanaka o laua, i na apana eha, okoa kanaka nui, okoa kanka [sic] malalo iho o lakou, okoa kanaka liilii, okoa kamalii. (Aole i pau.) | ʻUmi then ascended into the uplands, to where Kaleiokū and the others were farming with the people. When Kaleiokū was found farming with their people, Kaleiokū asked of ʻUmi, "Have those old men arrived?" ʻUmi nodded. "Yes, they have arrived. The things you taught me to prepare for their arrival, that is, the food. I prepared it all until it was complete. Those old men became dizzy from the ʻawa, and are now sleeping." Kaleiokū spoke to ʻUmi, "Let us stay here with your people, and when the sun begins the descend, we shall return. That is how we shall return. I will be the first of the people, and you, the Aliʻi, shall be the very last." And so it was, agreeable, in the eyes of ʻUmi. The reason why Kaleiokū chose to have the people of the aliʻi return together in a line, is because when they would arrive in front of the old men, they would speak with the first person they encountered. Because the old men would inquire to Kaleiokū about ʻUmi, and Kaleiokū would be the one to explain to them that they had been mistaken about this man. That man was ʻUmi. Because Kaleiokū was familiar to their eyes. They had not seen ʻUmi before, and would be in the dark of night when he returned from the uplands. That is what would bring the Island of Hawaiʻi under the control of ʻUmi. Their shame. When ʻUmi was ascending towards the uplands to look for Kaleiokū and the others, the old men were sleeping. Soon after, the second of the old men woke up, and the two conversed with each other. They said to each other, "This is not how our chiefs treated us in their reigns. During the time of Līloa, until he passed on, and during that of Hakau his child, food, fish and kapa were the things we received. Ours was but a small filthy house. This, however, is the best that we have ever seen. From the days of our handsome youth until this time of our old age, only now have we received these gifts of goodness. In our days of better health, we had none of this." As the sun descended, perhaps at about 2 o'clock, the descent of the journey began. Kaleiokū was the first as they descended. When the old men saw their descent, because there were so many people before their eyes, they could not see the last of the people descending as they emerged from within the tall trees of the forest of that ʻāina, which was spoken of in Chapter 2 of this moʻolelo (Waipunalei, in Hilo Palikū.) When Kaleiokū arrived in the presence of those old men, they expressed aloha for each other. It was the first time they were meeting again, and they had a great amount of aloha for each other. When the people returned to their houses, close to the house where they were staying, (that is, the hale o mua). These were just the tall people who had arrived at the village. Kaleiokū had divided their people into four groups: the biggest people, the people just under them, the small people, and the children. (To be continued.) |

* Simeon Keliikaapuni. "He Moolelo no Umi." Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. March 1, 1862.

* Translation by Kealaulili, 2014.

* Translation by Kealaulili, 2014.

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

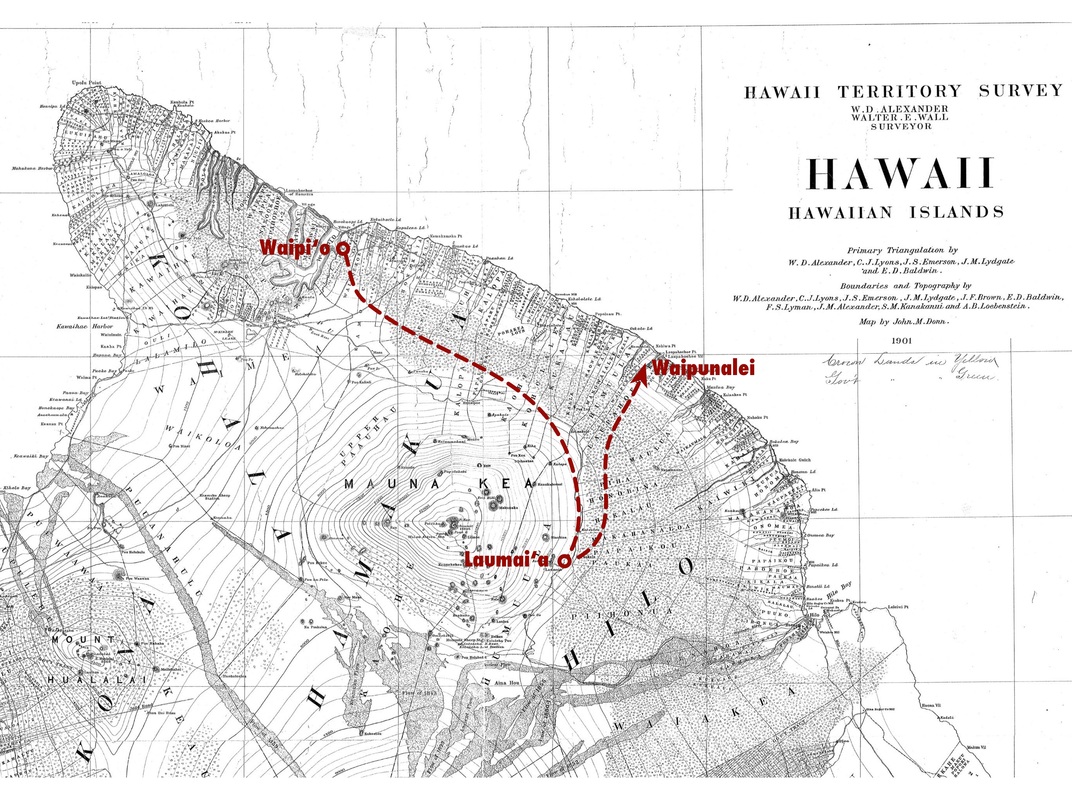

Helu 4.E na hoa hele o ke ala ulili, aloha kakou. E nana hou kakou i ka huakai hele a kela mau elemakule elua mai Waipio aku a i kahi i noho ai o Kaleioku a me kana hanai o Umi i Waipunalei. Wahi a Abraham Fornander, "pii aku la laua mai Waipio aku a hiki ma Kukuihaele, malaila aku a Kapulena moe. A ao ae la, pii aku la laua a hala o Honokaa, a Paauhau, moe, malaila aku a Kalopa, a Kaumoali, a Kemau, moe." (Vol. 4, Aoao 191) I ka poaha o laua nei ma ke alanui, lohe aku la o Kaleioku i kekahi poe, e hai aku ana ia ma ka inoa o ua mau wahi elemakule nei. "Ei ae na wahi elemakule o Nunu, o Kamai [oia no o Kakohe, wahi a Kamakau a me Fornander (Mea Kakau)] ke hele mai nei i ke alanui, me ka pono ole," ninau aku o Kaleioku i ka poe i olelo aku ia ia. "A hea la laua hiki mai?" I aku ka poe i lohe ai oia, "Apopo, a kela la aku hiki mai." Ninau hou o Kaleioku i ua poe nei, "Heaha la ka laua huakai nui?" Pane hou aku ua poe nei ia ia, "E hele mai ana e nana i kau hanai, i ka pono, me ka pono ole, no ka mea, ua hanai mai nei ka laua hanai o Hakau i na mea ino ia laua." Alaila, lohe iho la o Kaleioku me Umi, i ke kumu o ka hele ana'ku a ua mau elemakule nei i o laua. Pahapaha ae la o Kaleioku, me ka olioli loa, no ko Kaleioku manao, e lilo ka aina ia Umi i kana alii, no ka mea, he kahuna kilokilo o ua Kaleioku nei, nolaila kona apo ana mai ia Umi e malama. I kekahi la ae, oia ka Poalima, hoomakaukau iho la o Kaleioku me na kanaka o laua i ai, i ia, puaa, moa, awa, ua lako ia imua o ko laua mau maka, a ua makaukau hoi. Aka, ua hana maalea no o Kaleioku, i mea e lilo ai o ka aina ia Umi, i lilo ia i pono nona, penei kana hana maalea ana. Kena aku la o Kaleioku i kekahi kanaka, e hele e oki pauku wahie, ua like ka nui me na kanaka elua e apo ae ai a puni pono ia laua, a o kona loa i hookahi anana a me iwilei, hoi mai kaka a liilii, a pua hou ae, a like no me ka mea a olua e amo mai ai, ka lilo no ia i pauku hookahi. I kekahi mau kanaka hoi, i kela puawa e ku mai la, e eli ae mawaho a puni, o ka puawa, a o kekahi mau kanaka i ka puaa, e nikiniki a paa, ua lako, a makaukau koke ia imiia o ko laua mau kanaka. I hoomakaukauia keia mau mea e Kaleioku, i mea e hana aku ai o Umi imua o ua mau wahi elemakule nei, no ka hoa ana i ka imu, alaila, kii aku o Umi, a ua pauku wahie nei, kaka iho, i helelei liilii aku ma o maanei. Alaila, kapa aku ua mau wahi elemakule nei he ikaika o Umi, a pela i ka puawa, me ka puaa i nikinikiia'i. Nana iho la o Kaleioku, ua lako, a makaukau keia mau mea ana i olelo aku ai imua o na kanaka o laua. Olelo aku o Kaleioku i kana alii, i ke ahiahi o ua la Poalima nei. "E ke 'Lii! apopo ka la o ko aina la pa ia oe, e hoolohe mai e ke alii, ina e malama oe i keia mau olelo a'u, apopo pa ka aina ia oe, i malama ole oe, aole e ola keia mau iwi ia oe, kaulai wale ia ae no i ka la." Alaila, ua oluolu ia i ko ke alii mau maka, e malama i kana olelo, hai mai la o Kaleioku i kana mau olelo imua o Umi kana alii. "E ke alii e moe kakou i keia po, a huli ke kau pii au iuka i na koele a kaua, me na kanaka a pau loa o kaua, aole he kanaka iho me oe, o oe wale iho no koe, a me ko mau wahine. I na e hoea mai na wahi elemakule i kakahiaka o ka la apopo, i ninau ma ko'u inoa, manao oe, o laua ia, hoomakaukau aku oe imua o laua, ma na mea i hoomakaukauia na laua, ma na mea ai, a me na mea a pau a laua e makemake ai e haawi aku oe na laua, i ka wa e ona ai i ka awa." Ae aku o Umi kana alii, ma kana mau olelo kauoha. I ka huli ana o ke kau o ua po nei, pii aku la o Kaleioku me na kanaka o laua nei, a malamalama ae oia ka la Poaono, pau loa kanaka i ka pii iuka, koe o Umi me kana mau wahine elua. (Aole i pau) | Chapter 4.Oh traveling companions of the ala ʻūlili, aloha to you all. Let us look again to the journey of those two old men from Waipiʻo the place where Kaleiokū and ʻUmi were living at Waipunalei. According to Abraham Fornander, "they ascended the cliff of Waipiʻo, and arriving at Kukuihaele, they continued to Kapulena and rested there. On the next day, they continued their ascent, passing Honokaʻa, and arriving at Pāʻauhau where they again rested. From there, they went to Kalōpā, Kaumoali, and at Kemau rested again. On the fourth of their nights on the trail, Kaleiokū heard some people speaking the names of those two old men. "The old men, Nunu and Kamai [that is Kakohe, according to Kamakau and Fornander (Writer's Note)] are traveling here on the pathway, because pono has been lost." Kaleiokū then asked the people speaking to him, "When with they be arriving?" Those listening to him responded, "Tomorrow will pass, and the day after they will arrive." Kaleiokū again asked of those people, "What is the reason for their journey?" They then responded, "To come and see your hānai, and whether he is pono or not, because, their hānai, Hakau, has adopted hatred towards them." Thus, Kaleiokū and ʻUmi heard the reason for those old men traveling to see them. Kaleiokū boasted with great joy, for it was Kaleiokū's thought that the ʻāina would come under the control of ʻUmi, his aliʻi, because Kaleioku was a kahuna kilokilo, an expert in observation and forecasting, and it was for that reason that he grasped ʻUmi and cared for him. On the next day, that is the fifth night, Kaleiokū and their people prepared food, fish, pork, chicken, and ʻawa. All was well-supplied and well-prepared before their eyes. Kaleiokū, however, was crafty in his work. So that the ʻāina would come under the control of ʻUmi, and so that pono would come to him, this was the art of his craft. Kaleiokū commanded one person, "Go cut pieces of firewood, to the amount equal to that of which two people could grab and surround themselves completely with. And the length of each being one anana (length between tips of finger with arms spread open) and an iwilei (length from collar to tip of finger with arm extended). When you return chop them into smaller pieces and bundle them up, just as you had done in grabbing them, and that will become one pile." And to some other he said, "That ʻawa plant standing there, dig completely around it and the root ball." And to some others he requested they get the pig, and tied it up tightly. All was well-fashioned and immediately prepared that was sought out by their people. These things were prepared beforehand by Kaleiokū so that ʻUmi would be able to complete these tasks before those old men. To light the imu, then ʻUmi would just need to fetch the bundle of firewood, chop them up smaller, and scatter a little here and there. And then the old men would call ʻUmi a strong person, as he would also have prepared the ʻawa root, and the pig the had been tied up. Kaleiokū looked around, before their people he said, all is well-fashioned and prepared. In the evening of that fifth night, Kaleiokū told his aliʻi, "Oh Chief! Tomorrow is the day that your ʻāina will be secured to you. Listen to me, oh aliʻi. If you heed these words of mine, tomorrow, the ʻāina will be secured by you, and if you do not heed them, then these bones will not live through you. They will be left to dry out in the sun." It then became apparent in the eyes of the aliʻi, that he should heed his words. So Kaleiokū spoke his words before ʻUmi, his aliʻi, "Oh chief, we shall sleep tonight, and when the late of night passes before dawn, I will ascend to the farm patches of ours with all our our people. No one will stay back with you. You will be the only one remaining with your wahine. If the two old men arrive tomorrow morning, and they ask of my name, you will know that it is them. Go and prepare for them, all the things that have been prepared beforehand for them, the food, and anything that they should want, you will give to them, when they are delighted by the ʻawa. ʻUmi, his aliʻi, agreed to his command. When the late of that night passed before dawn, Kaleiokū and all of their people ascended the uplands. And when the light of the sun shown on that day, all of the people had gone into the uplands, leaving only ʻUmi and his two wahine. (To be continued) |

*Original text: Simeon Keliikaapuni. "He Moolelo no Umi," Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. Feb. 22, 1862.

*Translation by Kealaulili.

*Translation by Kealaulili.

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

Auhea oukou e na hoa heluhelu o ke ala ulili, mai kahi kihi a kahi kihi o ko kakou kulaiwi o Hawaii, aloha nui kakou. Eia no kakou ke hoomau aku nei i ke kuamoo olelo o ko kakou alii kaulana, o Umi-a-Liloa hoi, a ina ua hele a luhi ke kino i ka loihi o ka hele ana i ke ala ulili, e noho pu oukou i ka lokomaikai o keia alii no Hamakua. Ma keia wahi mahele o ko kakou moolelo, e ike ana kou maka i na hana i kaulana ai keia alii, na hana hoi i hoopaa ia e ke alii maoli, e ke alii pono, a i kiahoomanao kona moolelo no kakou, na mamo e ola nei, i mea e ike ai kakou i ka pono a me ka pono ole o ka noho aupuni ana. I alii no o Umi i na kanaka ana i malama ai, oia hoi, ke kanaka nui a me ke kanaka iki, a oia no ke kumu i olelo ia ai keia olelo noiau e ka poe kahiko, "Hookahua ka aina, hanau ke kanaka. Hookahua ke kanaka, hanau ke alii." No laila, e ka poe aloha aina o ko Hawaii nei Paeaina, e hoomau kakou. | Dear reading companions of the ala ʻūlili, from one corner to the other corner of our beloved homelands of Hawaiʻi, aloha to you all. Here we are continuing along the path of tradition of our famous aliʻi, ʻUmi-a-Līloa, and if perhaps your body has become weary from the long journey along the steep trails, then sit and rest here with the generosity of this aliʻi from Hāmākua. In this portion of our moʻolelo, your eyes with bare witness to the deeds that made famous this aliʻi, the deeds that are tended to by a true aliʻi, a pono aliʻi. For this moʻolelo stands as a reminder for us, the living descendants today, so that we may come to know of what establishes pono, or disturbs it, in the work of governance. ʻUmi was an aliʻi by the will of the people he cared for, that is, the "big person" and the "small person," and it is for this reason that the people of old would speak of these wise words: "The ʻāina creates the foundation upon which the people are born. The people create the foundation upon which the aliʻi are born." Therefore, dear aloha ʻāina, dear people who love this ʻāina of our Hawaiian Islands, let us continue on. |

Helu 3.Alaila, hoi aku la o Umi me Kaleioku, a noho iho la ma kona wahi, a noho iho la laua malaila [ma Waipunalei]. O ka hoomaka iho la no ia o Kaleioku e hana. O kana hana i hana'i, i mea e lilo ai ke aupuni no kana alii no Umi, no ka mea, ua maopopo ia ia he alii keia, he hanai kanaka, hanai holoholona, puaa, a me ka moa, he mahiai, he ao i ka makaihe, no ia hale ao mai kekahi mau kanaka akamai i ka pana laau, (oia o Koi, Omaokamau, a me Piimaiwaa.) I ko Umi ma noho ana ilaila, ua liuliu loa. A iloko oia noho ana, nui mai na kanaka, o ka nui o na kanaka he eha kaau, ua like ia me 160 hale, i ke kaau hale hookahi, hookahi lau kanaka, a pela a pau na kaau hale eha, eha lau ia o na kanaka, ua like paha 1,600 ka nui. A pela no o Kaleioku i hoolako ai no kana alii, i na mea a pau e makaukau ai. No ka manao o ua Kaleioku, e lilo ke aupuni i kana alii, oia kona mea i hoomakaukau ai i na kanaka, i ke ao ana i ka makaihe. E ka mea heluhelu, eia mai kekahi lālā o kēia kuamoʻo ʻōlelo no ko ʻUmi noho ʻana me Kaleiokū. Wahi a S. M. Kamakau, "I ka lilo ana o Kaleioku i kahu hanai no Umi. O ka hanai no ia i kanaka, a piha ua halau a piha ua halau, a umi a umi na halau i paha i kanaka, hele mai kanaka o Hilo i ka paakai i Hamakua, a ua hanaiia i ka puaa, a o ko Hamakua huakai a me ko Kohala a me ko Kona, e hele ana ma Hilo a Puna i ka hulu, a hookipa ia lakou ma kahi hanai kanaka o Umi. Aole i hala ka makahiki, ua kauluwela ka nui o na kanaka, a ua kaulana ka lokomaikai o Umi, aia na kanaka a pau o ka mahiai ka hana nui, a i ke ahiahi o ke ao i na mea kaua, alaila kukui aku la ka lohe a hiki i Waipio, aia o Umi la me Kaleioku kahi i noho ai, he alii lokomaikai, he malama i ke kanaka nui i ke kanaka iki, i ka elemakule, i ka luahine, i ke keiki, i ka ilihune, i ka mea mai." (Ke Au Okoa, Nov. 17, 1870.) | Chapter 3.Thus, ʻUmi returned with Kaleiokū, and the two stayed together there at his residence [at Waipunalei]. And so the work of Kaleiokū immediately began. His work was that which would ensure that the kingdom would be ruled by his aliʻi, ʻUmi. For he understood that ʻUmi truly was an aliʻi. He fed the people. He fed the animals, pigs and the chickens. He was a farmer. And he was well learned in the use of a spear, coming from the same school as that of other men skilled in the use of bows (that is, Kōī, ʻŌmaʻokāmau, and Piʻimaiwaʻa). During ʻUmi's residence there, he remained for a significant period of time. Within that period of residence, a great number of people came to live there. The number of people was equal to that of four kaʻau (x40), that being, 160 houses. Within one kaʻau (group of 40) houses was one lau (400) of people, and so it was for each kaʻau of houses, equalling to four lau of people, that being 1,600 people total. That was how Kaleiokū supplied his aliʻi, with all the necessities to prepare him. For it was Kaleiokū's intention to bring the kingdom under the rule of his aliʻi. That is why he prepared the people with lessons in fighting with spears. Oh reader, here is another branch of this path of tradition regarding ʻUmi's residence with Kaleiokū. According to S. M. Kamakau, "When Kaleiokū became a guardian for ʻUmi, they began to feed the people until each and every hālau was filled. Tens upon tens of hālau were filled with a multitude of people. When the people of Hilo went to Hāmākua for salt, they were fed pork. And when those of Hāmākua, Kohala, and Kona journeyed to Hilo and Puna for feathers, they were greeted at the place where ʻUmi fed his people. Without even a year passing, the people were swarming in numbers, and the generosity of ʻUmi became well-known. The main work of the people was in farming, and in the evenings the things related to battle were taught. Eventually, word spread as far as Waipiʻo that ʻUmi was in residence with Kaleiokū, and that he was a generous aliʻi. He cared for the "big person" and the "small person" for the elderly men and women, for the children, for those in destitution, and for the sick." |

No Nunu me Kakohe

Regarding Nunu and Kakohe

Regarding Nunu and Kakohe

| Ua loohia na wahi elemakule kahuna a Hakau i ka mai. Inu laau hoonaha ua mau wahi elemakule nei, a naha iho la ko laua mau apu, a pau ka inoino o ko laua mau opu, ia manawa koke no, olelo aku la laua i ko laua kanaka, e hele i o Hakau la i ko laua haku. No ka mea, he punahele ua mau wahi elemakule nei, ia Liloa i ka makuakane o Hakau me Umi, eia ke kumu i punahele ai laua ia Liloa. Aia ia laua ka malama o Kaili ke akua o ua Liloa nei, ia laua wale no e hiki ai, aole i kekahi mea e ae. I na no ke kaua mai, hele aku no o Liloa ia laua, na laua no e hoole mai, "aole kaua," pau ae la no, a pela aku no i kela hihia o ke aupuni, keia hihia. A hiki i ka wa i make ai o Liloa, ua hooili ae i ka aina no Hakau. I ka wa i hele aku ai o kahi kanaka o ua mau elemakule nei imua o Hakau ke alii, ninau mai ke alii ia ia, "Heaha mai nei kau?" I aku ia, "I hele mai nei au imua ou o ke alii, na na wahi elemakule i hoouna mai nei, e hele mai au imua ou o ke alii, i ai, i i-a, i awa, no laua, i mea e hoopaa ai i ka naha laau o laua," pane mai la ke alii ia ia. "O hoi oe a ia laua hoole aku.'' Hoi mai ua kanaka nei, a hai mai i ka ke alii mea i olelo mai ai ia ia, imua o ua mau wahi elemakule nei, lohe iho laua, he mau olelo inoino loa ka ke aili no laua, loaa ia laua ka ohumu ma ko laua naau, (lilo ka aina ia Umi la.) I ka wa i noho iho ai mahope iho o ka lohe ana i na olelo a ke alii, kaumaha ko laua nei manao, me ke kahaha nui loa, olelo aku kekahi wahi elemakule, i kekahi elemakule, "Pehea la ka Kaleioku hanai, e loheia mai nei? E hele paha kaua malaila ?" Ae mai la kekahi elemakule, "Ae, e nana wale aku hoi kaua i ka maikai o kana hanai, me ka maikai ole," ua holo like ia i ko laua manao. Wahi a S. M. Kamakau, "Makemake iho la o Nunu a me Kakohe e ikemaka no ka mea, he kaikaina o Kaleioku no laua iloko o na makua hookahi, a he poe hoi mai ka pupuu hookahi mai, a mai ka papa kahuna mai hoi a Lono." (Ke Au Okoa, Nov. 17, 1870.) O ko laua nei hoomaka no ia i ka hele ana, o ko laua nei hele no ia, a poakolu laua nei i ke alanui, mai Waipio aku laua nei ka hele ana 'ku, e hele ana laua i Hilo, ma ka aoao akau aku o Hamakua. (Aole i pau) | The elderly kahuna of Hakau were overwhelmed by sickness. These elderly men drank a purgative medicine, and when their coconut shell cups were taken, the pain in their stomachs resided. At that moment, they told their attendants to go to their chief, Hakau, because these old men were favorites of Līloa, the father of Hakau and ʻUmi. Here is the reason for Līloa favoring them. Theirs alone was the task of caring for Kāʻili, the akua of Līloa, no one else could do the same. If war was imminent, Līloa went to them, and it was they who told him, "No war," and it was finished. And so it was for each and every difficulty of the kingdom, until the time of Līloa's passing arrived, and the ʻāina was inherited by Hakau. When one of the attendants of these old men went before Hakau, the aliʻi asked of them, "What is your business here?" The attendant responded, "I have come before you, oh chief, because the old men have sent me to come before you to request some food, fish, and ʻawa for them, so that the purgative medicine they took can be complete." The aliʻi responded to them, "Return to them and tell them no." Their attendant then returned to them and told them what the aliʻi had said. When they heard that the aliʻi had only very wicked words for them, a plot of conspiracy developed in their naʻau (rule of the ʻāina would be taken by ʻUmi). In the time they spent after the words of the aliʻi were heard, their thoughts were burdened by great displeasure. One of the old m"en said to the other, "What about the hānai of Kaleiokū that we heard about? Perhaps we should go there?" The other old man agreed, "Yes, let us go see for ourselves what is good and perhaps not good of his hānai." Their thoughts were in alignment. According to S. M. Kamakau, "Nunu and Kakohe wanted to see for themselves, because Kaleiokū was a kaikaina (younger familial relative) of theirs, coming from a common parent, that is, they came from the same womb, and from the priestly class of Lono." And so they began their journey. They traveled for three nights along the trail from Waipiʻo heading towards Hilo, on the northern side of Hāmākua. (To be continued) |

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

E na hoa makamaka o ke ala ulili, ua hiki mai nei kakou i kekahi mahele nui o nei moolelo, a e ike ana kakou i ke ano haipule o ke alii i kona wa e noho ilihune ana ma Laupahoehoe a i kona noho aupuni ana i ke kuapapa nui ana o ka moku iaia. He ano kaulana keia ona, a wahi a kahiko, o ke alii haipule i ke akua, oia ke alii i ku i ka moku. Nolaila, e na hoa heluhelu, e iho kakou i kai o Laupahoehoe a e hoomau aku kakou i ke kuamoo o ka mea nona keia moolelo, oia no o ke alii kaulana o Hamakua, o Umialiloa. | Oh companions of "the steep trail," we have arrived at an important part of this moʻolelo, and we are about to see the pious nature of the aliʻi during his time living in destitution in Laupāhoehoe, until the time in which he reigned, after having unified the island under him. This was a famous characteristic of his, and according to the traditions of old, the aliʻi who worshipped the akua was the aliʻi who would rule the island. Therefore, oh reading companions, let us descend to the shore at Laupāhoehoe, and we shall continue along the path of the one for whom this moʻolelo is written, that is, the famous aliʻi of Hāmākua, ʻUmialīloa. |

No ko ʻUmi Noho ʻIlihune ʻana ma Laupāhoehoe

ʻUmi's Life in Destitution at Laupāhoehoe

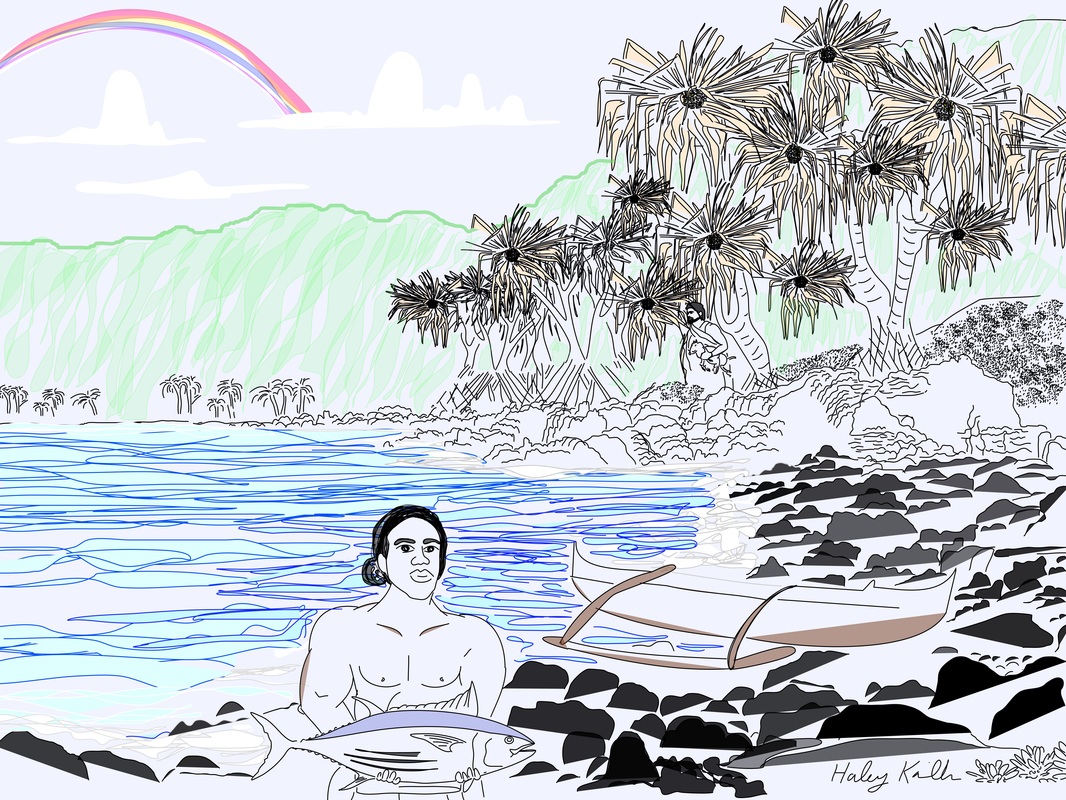

Helu 2 (Hoʻomau ʻia)I ko lakou noho ana malaila [ma Waipunalei], kuka lakou e huna ia Umi, aole e hai i kona inoa; kuka hou lakou, aole e hana o Umi, e noho wale no, a noho wale o Umi e like me ko lakou manao. A i ko lakou liuliu ana malaila, hele aku o Piimaiwaa, a me Koi, me Omaokamau, e mahiai ma ke kihapai o ko lakou makuahonowai aka, o Umi ka i hele ole. I ko lakou hoi ana, mai ka mahiai mai, olioli ko lakou makuahonowai no ko lakou ikaika i ka mahiai. Aka, o ko Umi mau makuahonowai, kaumaha loa no ko Umi ikaika ole i ka mahiai no kana wahine. A i kekahi wa, hele lakou ma kahakai o Laupahoehoe, he akamai o Umi i ke kahanalu, a heihei ana, hooke ikaika mai o Paiea [he kanaka akamai i ka heenalu no Laupahoehoe] ia Umi [i ka pohaku], eha loa ko Umi poohiwi ia Paiea, oia ko Paiea hewa i make ai ia Umi, i ko Umi wa i ku ai i ka moku. A hiki i ke kau Aku o ua wahi la, holo o Piimaiwaa, Omaokamau, me Koi, i ka hoe Aku me kamaaina o ia wahi. I ka wa i loaa mai ai ka lakou Aku, olioli ko lakou mau makuahonowai; aka, o ko Umi mau makuahonowai, kaumaha loa no ko Umi holo ole i ke kaohi Aku me na lawaia o ia wahi. I mai na makuahonowai o Umi i kana mau wahine. "Ina paha ka puipui o ka olua kane, he kanaka lawai-a, ina ua aina ke Aku; aka, makehewa ko olua mau kino ia ia." I kekahi manawa, ike mai na lawai-a he kanaka puipui o Umi, i mai lakou ia ia e hele i ke kaohi Aku, ae aku no o Umi i ka lakou olelo, aole nae lakou i ike he alii o Umi; aka, ua kaulana loa ka nalo ana o Umi. Aole nae lakou i ike o Umi keia. I ko Umi holo ana e kaohi Aku i ka wai, haawiia mai ai kana Aku e ka lawai-a, ike aku o Umi, ua polalo mai ka lawai-a i ke Aku malalo o ka lemu, aole o Umi i lawe ia i-a nana. Aka, kuai aku o Umi i kana ia me ke kaohi e, ka mea i haawiia mai kona ia maluna mai, i mai o Umi, "Homai na'u kau i-a uuku, eia mai kau o ka i-a nui," ae mai kela kaohi. Aole o Umi i ai i ua i-a nei, lawe aku no na Kaili, (kona akua) aia no ma kahi o Hokuli, ko Umi wahi i huna ai. E ka mea heluhelu, e nana kakou i kekahi lala o keia kuamoo olelo no keia hana kapanaha a Umi. Wahi a Samuel M. Kamakau, "I ka ike ia ana o Umi he kanaka ikaika, a ua makemake nui ia o Umi i kanaka kaohi malau aku, a ua makaukau io no, a ua ikaika maoli no i ka hoe waa. I kekahi wa, ua nui ka ia, a ua haawi pono ia mai ka ia, a i ka wa uuku o ka ia, ua poho lalo ia malalo o ka noho'na ke pakahikahi aku, alaila, ua haumia kela ia malalo o ka noho'na, a ua hoopailua ke akua aole pono ke hoali aku na ke akua, a nolaila, ua kuai ia me ke kanaka i loaa pono ka ia maluna pono mai, aole ma ka noho'na, a ina hookahi wale no wahi ia, aole e ai o Umi, ua waiho no oia na kona akua na Kukailimoku, aia ma ke ala iho o Hokuli [he pali ia], a ua huna ia iloko o ke ana; a no ka ikaika o Umi i ke kaohi aku a me ka hoe waa, ua kapaia o Puipui-a-kalawaia." (Ke Au Okoa, Nov. 17, 1870.) I kona holo pinepine ana i ka lawai-a, haohao o Kaleioku [he kahuna oia] i ka pio mau o ke anuenue ma ia malau. Manao o Kaleioku, o Umi paha kela; no ka mea, ua loheia ko Umi nalowale ana. Alaila, iho mai o Kaleioku me ka puaa, a ike oia ia Umi e noho ana me ka hanohano, a manao iho la o Kaleioku, he alii keia. Alaila, kaumaha aku la oia i ka puaa, me ka i aku, "Eia ka puaa e ke akua, he puaa imi alii." I ka Kaleioku kuu ana'ku i ka puaa, holo aku la ka puaa a ku ma ko Umi alo; alaila, huli hou mai ua puaa nei ia Kaleioku. Ninau aku o Kaleioku, "O Umi anei oe?" Ae mai o Umi, "Ae, owau no." I aku o Kaleioku, "E hoi kaua i ko'u wahi." Ae mai no o Umi; alaila, i ae la kona mau makuahonowai, a me kolaila mau kanaka a pau. "He alii ka keia! o Umi ka ia!! o ka Liloa keiki ka!!! ka mea a kakou i lohe iho nei i keia mau la, ua nalowale." (Aole i pau) | Chapter 2 (Continued)As they settled in there [at Waipunalei], they discussed concealing 'Umi, and not speaking his name. They further discussed that 'Umi should not work, but just rest. And so 'Umi consented with their wishes. As they remained there for some time, Pi'imaiwa'a, Kōī, and ʻŌmaʻokāmau began to go and cultivate the fields of their wahine's parents, but ʻUmi did not go. When they returned from their farming, the parents of their wahine rejoiced in their strength as farmers. However, the parents of ʻUmi's wahine were deeply bothered by ʻUmi's lack of effort in farming for his wahine. At another time, they went to the ocean at Laupāhoehoe. ʻUmi was very skilled in body surfing, and in one particular contest urged on by Paiea [a skilled surfer of Laupahoehoe], ʻUmi was crowded [into the rocks] by Paiea, and ʻUmi's shoulders were struck and injured. That wrongdoing of Paiea is what brought death to him by ʻUmi, when ʻUmi later ruled the island. When the aku season arrived at that place, Piʻimaiwaʻa, ʻŌmaʻokāmau, and Kōī went out aku fishing with the kamaʻāina of that place. When the time came that they caught their aku, the parents of their wahine again rejoiced. But the parents of ʻUmi's wahine were troubled by ʻUmi's refraining to go catch aku with the fishermen of that place. These parents of ʻUmi's wahine said to their daughters, "If your strong, able-bodied kāne was perhaps a fisherman, then the aku would be yours to eat, but your bodies are being wasted upon him." At another time, the fishermen saw that ʻUmi was a sturdy man, so they told him to come aku fishing with them. ʻUmi agreed to their request, but they did not see that he was an aliʻi. Though it was well known that ʻUmi was in hiding, they did not know that this indeed was ʻUmi. When ʻUmi went out to catch aku in the water, he was given a fish by the other fishermen, but ʻUmi saw that the fisherman had reached between his legs and grabbed the aku from under his buttocks. So ʻUmi did not take that fish for him. Instead, ʻUmi traded his fish with the one who had withheld the fish taken from above for himself. ʻUmi said to him, "Give to me your small fish. Here is yours, a big fish," and that withholder agree. ʻUmi, however, did not eat that fish. It was taken and offered to Kāʻili (his akua), at a place called Hokuli, where ʻUmi had hidden it. Oh reader, let us now look at another branch of this path of tradition about these wonderful deeds of ʻUmi. According to Samuel M. Kamakau, "When it was seen that ʻUmi was a strong man, many desired that he join them in aku fishing, for he was indeed skilled and truly strong as a canoe paddler. At times, when the fish were abundant, the fish was given out in a pono way. However, in times when the fish were scarce, they were dealt dishonestly from beneath the seat when apportioned out. Those fish from below the seat were then haumia (defiled), and the akua would become offended by it if it were offered to the akua. Therefore, an exchange would be made with someone who received fish in a pono way, from above rather than below the seat. And if there was only one fish, ʻUmi would not eat it. He would leave it for his akua, Kūkāʻilimoku, which was hidden inside of a cave along the trail descending Hokuli [a cliff]. Thus, because of his skill and strength in aku fishing and canoe paddling, ʻUmi was called "Puʻipuʻi-a-ka-lawaiʻa" (Stalwart fisherman). As he began regularly going out fishing, Kaleiokū [a kahuna] marveled at the frequent appearance of the arching rainbow above those calm aku fishing grounds. Kaleiokū thought, perhaps that was ʻUmi, because ʻUmi's disappearance had been heard of. Therefore, Kaleiokū descended with a pig, and he saw ʻUmi sitting there in a dignified manner. Kaleiokū then thought to himself, this is a chief. He then lifted the pig and spoke thus, "Here is the pig, oh akua, a chief-seeking pig." Then as Kaleiokū released the pig, the pig ran forth and stood before ʻUmi, then turned back towards Kaleiokū. Kaleiokū questioned, "Are you perhaps ʻUmi?" ʻUmi nodded, "Yes, it is I." Kaleiokū then said to him, "Let us return to my place." ʻUmi agreed, and then the parents of his wahine, and all the people of that place spoke out, "This is an aliʻi! It is ʻUmi!! Līloa's child!!! The one we had all heard over these past days, had disappeared!" (To be continued) |

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

No ka heʻe malu ʻana ʻo Umi mā mai o Hakau aku.

The Escape of ʻUmi & his Keiki Hoʻokama from Hakau

Helu 2 (Hoʻomau ʻia)I ka make ana o Liloa, noho aku o Umi malalo o Hakau, a nui no hoi ko Hakau huhu mai ia Umi, a nui no ka hokae mai ia Umi. I ko Umi wa e heenalu ai i ko Hakau papa, i mai o Hakau ia Umi, "Mai hee oe i ko'u papa; no ka mea, he makuahine noa wale no kou ma Hamakua, he kapu ko'u papa, he alii au." I ko Umi hume ana i ko Hakau malo hokae mai o Hakau me ka i aku ia Umi, "Mai hume oe i kuu malo, he alii au; he makuahine kauwa kou no Hamakua." Pela no o Hakau i hoino ai ia Umi, ka hookuke maoli; alaila, hee malu o Umi mai o Hakau aku. Eia ko Umi mau hoa hele, o Omaokamau, o Piimaiwaa, o laua kona mau hoa hele mua mai Hamakua mai a Waipio. I ko lakou hoi hou ana i Hamakua, mai Waipio aku, ma ko lakou ala i hele mua mai ai i ko lakou pii ana'ku ma Koaekea, hiki lakou ma Kukuihaele, alaila, loaa ia lakou o Koi, alaila, hele oia me Umi. I ko lakou hele ana'ku a hiki lakou i Kealahaka, oia ko Umi wahi i hanau ai, aole lakou i kipa i kona makuahine; no ka mea, ua manao lakou e hele kuewa wale aku. E na hoa heluhelu, e oluolu e hoomaha kakou ma keia wahi o ke kuamoo o ke alii kaulana nona keia moolelo, a e huli kakou e nana aku i kekahi lala o keia kuamoo olelo. Wahi a kekahi mea kakau kaulana o Hawaii, o Samuel M. Kamakau, i Waikoekoe ma Hamakua i loaa ai o Koi ia Umi ma i ko lakou hele mua ana aku i Waipio mai Kealakaha aku. Ia Koi e koi ana ma kae alanui, loaa o Umi iaia a ua lilo ihola o Koi i keiki hookama na Umi. Eia ka Kamakau i kakau ai no ko Umi hee malu ana mai o Hakau aku. (Mea Kakau) | Chapter 2 (Continued)Upon the death of Līloa, ʻUmi lived under Hakau. Great was Hakau's anger towards ʻUmi, as were his attempts to completely erase ʻUmi from existence. When ʻUmi went surfing on Hakau's board, Hakau said to ʻUmi, "Do not surf on my board, because you have a commoner mother in Hāmākua, and my board is kapu. I am an aliʻi." When ʻUmi girded Hakau's malo, Hakau seized ʻUmi and told him, "Do not gird my malo. I am an aliʻi. You have a lowly servant mother from Hāmākua." That is how Hakau mistreated ʻUmi, with the true intention of driving him away. Therefore, ʻUmi sought protection in escaping Hakau. ʻUmi's traveling companions were ʻŌmaʻokāmau and Piʻimaiwaʻa, those who had first traveled with him from Hāmākua to Waipiʻo. In their return to Hāmākua from Waipiʻo, along the path they traveled in their ascent of Koaʻekea, they arrived at Kukuihaele. It is there that they found Kōī, and he went along with ʻUmi. As they traveled back towards Kealakaha, the place where ʻUmi was born, they did not stop to visit his mother, for it was their thought to simply wander for a while. Oh reading companions, if you will, let us now rest at this place along the path of the famous aliʻi for whom this moʻolelo is written, and let us turn now towards another branch of this path of tradition. According to another famous writer of Hawaiʻi, Samuel M. Kamakau, it was at Waikoʻekoʻe in Hāmākua that ʻUmi and the others found Kōī, while they were first traveling to Waipiʻo from Kealakaha. While Kōī was playing kōī (a children's sliding game) alongside the trail, Umi found him and Kōī became a keiki hoʻokama of ʻUmi. Here is what Kamakau wrote about ʻUmi's escape from Hakau. (Author's Note) |

| Nolaila, ua mahuka o Umi a Liloa me kana mau keiki hookama, a no ka makau no hoi kekahi o Umi o make i ka pepehiia e Hakau, nolaila, ua mahuka malu o Umi ma, ma ka nahelehele mauka o Hamakua, a o loaa hoi kekahi ke hele ma ke alanui, a ma Puuaahuku [Puaahuku] ko lakou mahuka ana, a komo i ka lae laau, a o ke akamai o Piimaiwaa i ka uhai manu o ka nahelehele, a ua loaa no hoi ka ia a me ka lakou ai, a hiki o Umi ma i uka o Laumaia Kemilia, o Laumaia Kenahae, a noho lakou nei ilaila, alaila, hoouna mai la o Umi ia Piimaiwaa e hele mai e hai ia Akahiakuleana, aia ko lakou wahi i noho ai i uka o Humuula, aohe e hiki ia lakou ke hoi mai e noho pu lakou me na makua o Umi a Liloa, aka, ua olelo o Akahiakuleana, aole pono e hoi mai e noho pu, ua hiki aku ka imi a na Luna o Hakau ilaila. Olelo aku o Akahiakuleana, aole he pono ka noho ana ma na palena o Hamakua, e pono ke hele ma na palena o Hilo, no ka mea, ua kukaawale ka moku o Hilo ia Kulukulua, aole he mana o Hakau ma Hilo. A lohe o Umi ma i keia mau olelo a Piimaiwaa mai ka makuahine, ua hele aku lakou a noho ma na palena o Hilo e kokoke mai ana i ka palena o Hamakua, o na Waipunalei ka inoa oia mau wahi ahupuaa, a noho iho la o Umi a Liloa ma ua wahila, he nui na kanaka, a he nui no hoi ka wahine maka hanoahano, a mau kaikamahine makua oia wahi, a he poe kanaka ui wale no, a o Umi a Liloa aku no ka oi o lakou i ka oi o ka ui a me ke kanaka maikai, a nolaila ua loaa papalua, a papaha ka wahine ia Umi, a i na keiki hookama, ua loaa ia lakou na wahine. I ko lakou noho ana ilaila, ua olelo aku na keiki hookama ia Umi a Liloa, "E noho malie no oe o makou no ke mahiai, a ke kahu imu nana wahine a me na makuahonowai o kakou, e noho malie no oe." Nolaila, e na makamaka heluhelu, e noho pu kakou no ka manawa a e pupu ai kakou i keia hunahuna moolelo a he inai ono io no ia o na kupuna o kakou. E hoomau aku kakou i ke kuamoo o ke alii kaulana nona keia moolelo i keia pule ae, a e ike ana no kakou i na hana pono a Umi e hooko aku ai i ke kauoha kaulana a kona makuakane a Liloa, "E noho me ka haahaa." (Mea Kakau) (Aole i pau) | Therefore, ʻUmi-a-līloa fled with his adopted sons, because of ʻUmi's fear of being killed by Hakau. That is why ʻUmi them sought protection, fleeing to the forest in the uplands of Hāmākua, else they be captured while traveling along the trail. Puaʻahuku is where they fled to first and entered into the forest point. It was Piʻimaiwaʻa's skill in catching birds of the forest that allowed them to obtain their "fish" and food until they arrived in the uplands of Laumaiʻa Kemilia, Laumaiʻa Kenahae. They stayed there and ʻUmi sent Piʻimaiwaʻa to go to tell Akahiakuleana that the place they were staying was in the uplands of Humuʻula, and that they could not return to live with the parents of ʻUmi-a-līloa. Akahiakuleana told him that it was not good for them to return to stay with them because the scouts of Hakau had arrived there. Akahiakuleana further said, "It is not good to stay within the boundaries of Hāmākua. You must go within the boundaries of Hilo, because the district of Hilo remains independent under Kulukuluʻā. Hakau has no mana, no power, in Hilo." When ʻUmi and the others had heard these words of Piʻimaiwaʻa from his mother, they went to live within the boundaries of Hilo, nearby the boundary of Hāmākua. Nā Waipunalei was the name of these ahupuaʻa, and this is where ʻUmi and the others stayed. There were many people there. There were many women of magnificent appearance, and many well-developed women of that place. They indeed were a beautiful group of people, and ʻUmi-a-līloa was the most handsome of them all in appearance and physique. Therefore, the women of ʻUmi were twice, and four times as many in numbers as others. And so too for his adopted sons. They were taken by women as well. While they stayed there, his adopted sons said to ʻUmi-a-līloa, "You stay and rest here. We are the ones who will farm, and our wahine and their parents will tend to the imu. You stay and rest." Therefore, oh reading companions, let us stay here for the time being, and let us pūpū on this bit of our moʻolelo, a delicious relish of the ancestors of ours. We will continue along the traditional pathways of the famous aliʻi for whom this moʻolelo is written next week, and then we will come to know of the pono deeds of ʻUmi as he sought to fulfill the famous command of his father, Līloa, "Live with humility." (Author's Note) (To be continued) |

(Kamakau excerpt from "Ka Moolelo Hawaii," Helu 49. Ke Au Okoa. Nov. 17, 1870.)

Read Previous Installments: 1 - 2 - 3

A Moʻolelo for ʻUmi: A Famous Aliʻi of These Hawaiian Islands.

E nā hoa heluhelu o ke ala ʻūlili, eia nō kākou ke uhai aku nei i nā meheu kupuna ma ke ala o ko kākou aliʻi nui kaulana o Hāmākua nei ʻo ʻUmialīloa. E haele pū kākou a e ʻike ana paha kākou i nā hana kūpono o ko ʻUmi wā ʻōpio, ʻo ia nō nā hana i paʻa ai ke kahua o ko ʻUmi noho mōʻī ʻana. He waiwai kēia moʻolelo no kākou, ka lāhui aloha, i mea e ʻike ai i nā hana e paʻa ai ke kahua o ke aupuni pono. No laila, e nā makamaka, e hoʻomau kākou i kēia moʻolelo a Keliikaapuni i hoopuka mua ai, a e uhai pū kākou i ke aliʻi lokomaikaʻi o Hāmākua, ʻo ʻUmialīloa!

Oh reading companions of the ala ʻūlili, here we are following in our ancestral footsteps along the trail of our famous aliʻi nui of Hāmākua, ʻUmialīloa. Let us go forth together, and perhaps we shall come to know the righteous deeds of ʻUmi during the time of his youth, which solidified the foundation of ʻUmi's reign as mōʻī. This moʻolelo is of great value to us, the beloved lāhui, as a means of learning the works that make firm the foundation of a pono government. Therefore, dear friends, let us continue on in this moʻolelo that Keliikaapuni first published, and let us follow the generous aliʻi of Hāmākua, ʻUmialīloa!

Na Kealaulili, Mea Kākau

Koholālele, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi

June 14, 2014

Koholālele, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi

June 14, 2014