|

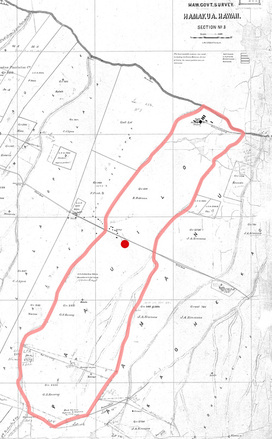

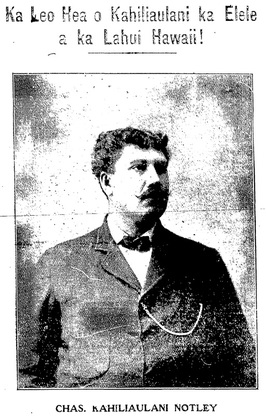

Every place has a name, and every name has a story. Here is one short story (of many untold) for a place whose name is familiar to many, but whose history is known by few. Here is a story of a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua. Whether you are a diehard Tiger or an occasional passerby, and definitely if you’re a born-and-raised kamaʻāina, there’s a good chance that Paʻauilo has influenced your life in some way. No joke. “That small country town?!” You might be thinking to yourself. Yeah. It doesn’t look like much to most, but I can assure you that if you are Kanaka and/or a kamaʻāina of Hawaiʻi Island, this place—now recognized as a “town,” whose name is derived from the ahupuaʻa in which it is located—has played some sort of role in your past, present (and if not, then future) experience of Hawaiʻi. So if you’re not from Paʻauilo, or Hāmākua, then let’s begin at the most basic, surface level: Earl’s. Chances are, if you’ve driven through Hāmākua on your way to Hilo or Waimea, you’ve stopped at Paʻauilo Store and bought a bento roll made by Earl’s. If you haven’t, pua ting you. Well maybe you didn’t happen to have cash on you when you stopped, so you just took the opportunity to use the porta-potty outside the store. Either way, Paʻauilo is generally a midway stop for commuters, cruising locals, or tourists, and a central hub for kamaʻāina of the area. It’s about 40 minutes from Hilo, and about 25 minutes from Waimea. So if nothing else, at the very very least, your belly and bladder can probably thank Paʻauilo for tiding you over on your long journeys. Okay, let’s kick it up a notch. Up until the early 1990s, Paʻauilo was smack-dab right in the middle of the island’s century-old sugar industry. Paʻauilo was a bustling plantation town made up of various “camps”—Old Camp, New Camp, Japanese Camp, Haole Camp, Nakalei—a school (home of the Paʻauilo Tigers), a store, a post office, a few churches, a ball park, and a couple generations of kamaʻāina, most of whom led humble lives shaped by sugar or cattle. A handful of my ancestors experienced Paʻauilo in this way, and developed a deep love and respect for this ʻāina, like many others. Those memories, however, remain beyond the realm of what my eyes have seen, and would best be shared by those whose eyes have. So let’s continue on this path, and talk a little more about what is unseen by most about this place.  1881 Map of the Ahupuaʻa of Paʻauilo (Reg. Map 855) Red dot indicates where Paʻauilo Store is today. 1881 Map of the Ahupuaʻa of Paʻauilo (Reg. Map 855) Red dot indicates where Paʻauilo Store is today. Paʻauilo, called “Pauilo,” or something close to “Pawilo” by most people today, is one of over 130 ahupuaʻa (ancestral land divisions) located in the district of Hāmākua. In the early 1800s, this ahupuaʻa was the kuleana of an aliʻi wahine by the name of Mikahela Kekauonohi. She was a high-ranking chiefly grandchild of Kamehameha I and kiaʻāina (governor) of Kauaʻi. As part of her "payment" to the government for lands received during the Mahele of 1848, Kekauonohi relinquished Paʻauilo to Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli), who later set the ahupuaʻa aside as part of the Government Lands of the Kingdom. Not long after, George S. Kenway and Robert Robinson, two haole men, purchased most of the ʻāina in this ahupuaʻa from the Kingdom government as Royal Patent Grants 2221, 2222, and 663—“Koe naʻe ke kuleana o nā kānaka”—"Subject to the rights of native tenants." These land sales would eventually plow the way for the establishment of large-scale sugar in the area. Prior to the Mahele, Paʻauilo, like other relatively small ahupuaʻa in Hāmākua Hikina (east Hāmākua), was likely home to about 150-200 Kānaka. Early European explorers and American missionaries described the area as fertile and highly cultivated, dissected by the multitude of streams that, now dry, once cascaded off the edge of Hāmākua’s sheer cliffs. One of these streams, Waipunalau, which forms the Kohala-side boundary of Paʻauilo (adjoining the ahupuaʻa of Paukiʻi), is fed by a spring named Waihalulu. Once favored by the kamaʻāina of Hāmākua Hikina for its “wai māpuna ʻono huʻihuʻi” (deliciously cold fresh spring water), Waihalulu was visited by Kamehameha I and his koa when they retired from the battle of Koapāpaʻa. Koapāpaʻa, located in the ahupuaʻa of Kūkaʻiau (just over a mile from Paʻauilo) was the site of the last battle fought by Kamehameha on Hawaiʻi Island in his campaign of unification. The 1791 battle began with Kamehameha holding a ceremony at Manini heiau in Koholālele, and ended with Keōua-kūʻahuʻula, the reigning chief of Kaʻū, seeking refuge under a large stone in Kainehe, which later came to bear his name: Pōhaku o Keōua. The battle proved to be a decisive victory for Kamehameha, as he soon gained control over the entire island.  Nā pali loa o Hāmākua. Photo by Author, 2015. Nā pali loa o Hāmākua. Photo by Author, 2015. But what was Kamehameha doing in Paʻauilo? Kamehameha was not the chief of Hāmākua. Kamehameha was from Kohala, and his primary alliances were formed with other Kohala and Kona chiefs. The aliʻi ʻai moku (district chiefs) of Hāmākua at the time that Kamehameha rose to power were Kānekoa and Kahaʻi, two chiefly brothers and uncles of Kamehameha. Both Kānekoa and Kahaʻi had actually fought against Kamehameha in the famous battle of Mokuʻōhai (in 1782, near Keʻei, Kona), defending Kīwalaʻō and his kālaiʻāina (chiefly redistribution of ʻāina). After Mokuʻōhai, Hāmākua came under the control of Keawemauhili, the highest ranking chief of the ʻĪ line alive at the time. Under his protection, Kānekoa and Kahaʻi remained until a disagreement forced them to flee the Hilo chief to go live under the Kaʻū chief, Keōua-kūʻahuʻula. The Hāmākua chiefs must have been quite independent in their thoughts and actions, because not long after settling in with Keōua, another fight ensued between the chiefs, leaving Kānekoa dead and his brother grieving.  "Hā-mākua" by Haley Kailiehu, 2013. www.haleykailiehu.com "Hā-mākua" by Haley Kailiehu, 2013. www.haleykailiehu.com During his mourning, Kahaʻi sought refuge in his nephew, Kamehameha. Kamehameha showed aloha for his uncles, recalling days when he was carried on their backs, and vowed to put an end to the Hilo and Kaʻū chiefs. It was these events, among a few others, that eventually brought the decisive battle to Hāmākua Hikina. It should be noted, however, that in his flight of defeat, Keōua was hidden and protected in Kainehe, by a kāhuna of the area, presumably with the support of the people of the area. Keōua represented the last of the ruling aliʻi of the powerful ʻĪ line that had kuleana over east Hawaiʻi (from Hāmākua to Kaʻū) since the time of ʻĪ, the great-grandson of the famous Umi-a-Liloa. The people of east Hawaiʻi were fiercely loyal to their chiefs of the house of ʻĪ, and those of the west held tightly to the Keawe clan. This battle between lineages was not a new one. It stemmed back to the generations that followed Umi’s unification of the island (about 16-17 generations before present). It seems only fitting, then, that the last battle in Kamehameha’s unification of our island would take place in the ʻāina hānau (birthplace) of ʻUmi, the great unifying ancestor from which both Keōua and Kamehameha descended. Hāmākua, then, was the "elder stalk" that held the ʻohana of moku together. Fast forward now a few generations to another time of vast political upheaval. Following the unlawful overthrow of the beloved reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Liliʻuokalani, in Honolulu, and the onset of the United States’ prolonged occupation of our islands, Kānaka and other loyal subjects of the Kingdom fought fiercely for the restoration of our country’s independence. In addition to the organizing of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina and Hui Kālaiʻāina that effectively defeated an impending treaty of annexation forced upon Hawaiʻi by those with imperialistic interests, Kānaka leaders in the struggle for independence from both Hui also formed the Independent Home Rule Party, nā Home Rula Kūʻokoʻa. Founded in 1900 by poʻe aloha ʻāina ʻoiaʻiʻo (people truly loyal to this ʻāina), Robert Wilcox, David Kalauokalani, and James Kaulia, the Independent Home Rule Party, as their name suggests, stood for the restored independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. And their battlecry was one rooted in unification.  from Ka Naʻi Aupuni, Nov. 5, 1906 from Ka Naʻi Aupuni, Nov. 5, 1906 As part of their campaign of unification, the party published two newspapers, first Ka Naʻi Aupuni (The Conqueror), and then, Kuokoa Home Rula (Independent Home Rule). Ka Naʻi Aupuni made clear whose responsibility it was to remedy the dire situation that the lāhui had found itself in: “Na Hawaii e Hooponopono ia Hawaii,” It is Hawaiʻi / Hawaiians that will bring pono to Hawaiʻi once again. The second paper, Kuokoa Home Rula, went further to remind us of the means by which we could fulfill this responsibility. “Ma ka Lokahi ka Lahui e Loaa ai ka Ikaika.” It is in Unity that the Lāhui obtains its Strength. Without actively enacting the “hui” in "lāhui," uniting together, we would cease to exist as a lāhui, a nation. This brings us back home to the place that this story began. The owner of both papers, and later, president of the Independent Home Rule Party, Charles Kahiliaulani Notley, was a home-grown kamaʻāina of no place other than Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi. Kahiliaulani was the son of Charles Notley, Sr. and Mele Kaluahine, a chiefly descendant of Keōua-kūʻahuʻula. In 1906, while running as the Home Rule candidate for "territorial" delegate to the US congress, Kahiliaulani gave a rousing speech before supporters of Home Rule, encouraging Kānaka to unite “no ka Pono, ka Pomaikai, ka Holomua, ka Lanakila, ame ka Hanohano o ka Lahui,” for the Pono, the Prosperity, the Advancement, the Victory, and the Dignity of the Nation. In closing his speech, Kahiliaulani like many of our contemporary Kānaka leaders, likened the path ahead for the nation to that of a voyage on rough seas. As was printed in Ka Naʻi Aupuni (Nov. 5, 1906), this part of his speech went as follows:

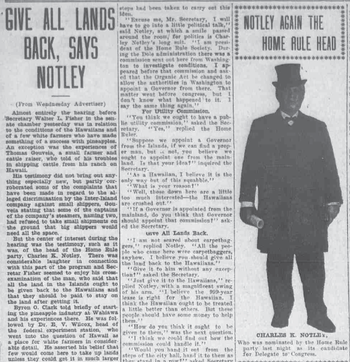

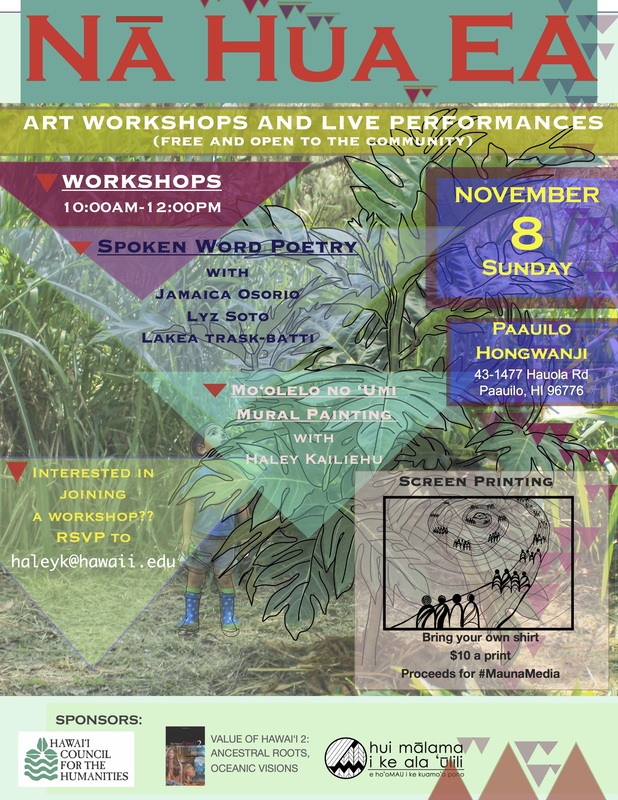

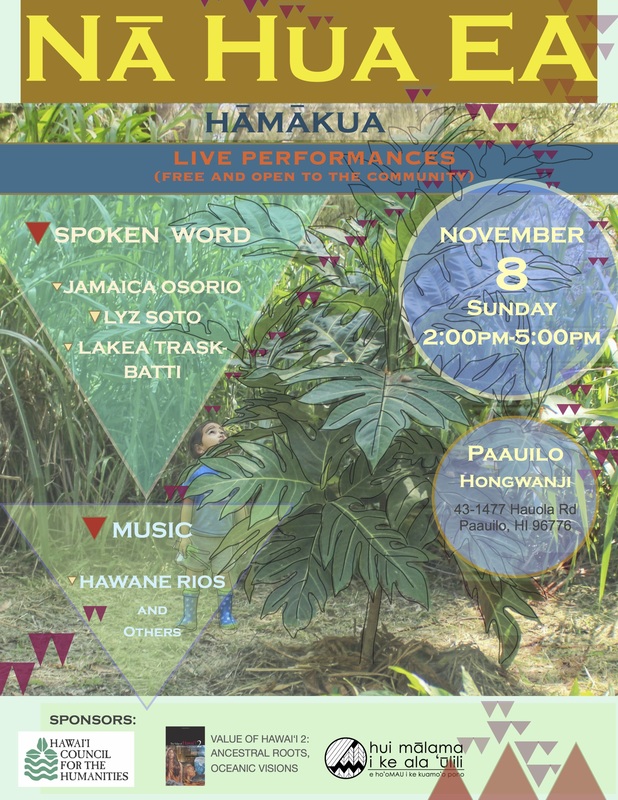

from the Hawaiian Gazette, Sept. 20, 1912. from the Hawaiian Gazette, Sept. 20, 1912. Now a commonly heard chant at Hawaiian gatherings of all sorts, “I Kū Mau Mau” was primarily invoked to inspire collective action when pulling a large felled tree down from the uplands (such as those on the slopes of Maunakea in Hāmākua), to be carved as a canoe or heiau image. Kahiliaulani’s invocation of it in his speech may be the first recorded usage of it in the context of contemporary Hawaiian politics. Though never successful in his campaigns to become a delegate to the U.S. congress, Kahiliaulani remained a fervently loyal Home Rula and Aloha ʻĀina, encouraging our people to “pull together” until the end. In fact, in a 1912 hearing regarding the conditions of Native Hawaiians, Kahiliaulani was quoted as having testified before then U.S. Secretary of the Department of Interior, Walter L. Fisher, that the U.S. should “give all the lands back to the Hawaiians.” According to the reporter from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, many of those present in the room chuckled at what seemed to be an unrealistic proposition. But Kahiliaulani did not waver in his conviction. Not only should all the lands be returned to Hawaiians, he insisted, but the government should also appropriate sufficient funds to support Hawaiians living and remaining on those lands. Imagine that. And just a little over a hundred years later, the U.S. Dept. of Interior is still getting an earful from the brilliant aloha ʻāina of this place. Surely Kahiliaulani is not the only historical figure from this unassuming place who deserves our praise and remembrance. He is but one of many who has been selectively honored in this moʻolelo—a moʻolelo which serves, really, to honor this place. After all, they are one and the same. And as is the responsibility of any storyteller, I will now conclude this moʻolelo where it began: in a quiet, old plantation town in Hāmākua. So the next time you pass by or stop at Paʻauilo Store, look ma kai across the street, and imagine Kahiliaulani once living there. And then look towards Hilo, and imagine the abundant days of Umi-a-Liloa’s youth or the awesome scene of over 30,000 koa converging in battle at Koapāpaʻa. Then look ma uka, and see the sacred summit of Mauna a Wākea, the highest peak in all of Oceania. Then look towards Kohala, towards the sacred valleys of Waipiʻo and Waimanu where generations of our most powerful chiefs once ruled. And remember why this place is called Hāmākua, "the parent stalk" of this island. And back here in the middle of it all you will find yourself, in a quiet, old plantation town, in Paʻauilo. (Aole i pau) Na Noʻeau Peralto Paʻauilo, Hāmākua, Hawaiʻi Oct. 14, 2015 In the same spirit of unification, Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili invites all in our community to join us for Nā Hua Ea on November 8, 2015 in Paʻauilo at the Paʻauilo Hongwanji. Nā Hua Ea is an art and poetry event collaboration between the editors of The Value of Hawaii 2, the Hawaii Council for the Humanities, and huiMAU, to bring together our community to create and share art and poetry that expresses our vision of Ea, genuine life, sovereignty, and well being. The day will begin with poetry and art workshops, open to the community, and culminates with an open mic performance. Please feel free to share the event flyers below. Mahalo!

15 Comments

|

Archives

November 2015

Categories |

Mahalo for visiting our Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili Website!

Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili is a community-based nonprofit organization. Our mission is to re-establish the systems that sustain our community through educational initiatives and ʻāina-centered practices that cultivate abundance, regenerate responsibilities, and promote collective health and well-being.

Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili is a community-based nonprofit organization. Our mission is to re-establish the systems that sustain our community through educational initiatives and ʻāina-centered practices that cultivate abundance, regenerate responsibilities, and promote collective health and well-being.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed