Ea - Video by Anianikū Chong, 2020

Ka Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea ma Hāmākua:

Celebrating our Abundance, Embracing our Kuleana, Breathing Ea into Our Future.

By Noʻeau Peralto, Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili

|

On July 31, 1843, the ea of Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina re-emerged through an act of pono. “Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono.” The reigning Mōʻī at the time, Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), said it best. “The ea (sovereignty, independence, life) of the ʻāina continues on, because it is pono.” For a little over five months leading up to that joyous day in July of 1843, the British flag flew above our beloved Hae Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian flag). On February 25 of that same year, Kauikeaouli had temporary ceded his sovereign authority as Mōʻī (reigning monarch) of the Hawaiian Kingdom to Great Britain after Lord George Paulet, commander of the British frigate Carysfort, had landed his warship in Honolulu and threatened the Mōʻī with violence. Paulet, acting on his own accord, had demanded an audience with Kauikeaouli just days earlier, while responding to a request from the British Consul to the Hawaiian Kingdom, Richard Charlton, to investigate claims of a property dispute between Charlton and the Hawaiian Kingdom government. After Kauikeaouli had refused to comply with his demands, Paulet threatened to attack the town of Honolulu with military force, compelling Kauikeaouli to temporarily surrender, under duress, his sovereign authority to Great Britain. As history tells us, Paulet proceeded to lower and destroy all the Hawaiian flags in his reach, raising the British flag in their place. This wrongful act marked the beginning of a five-month occupation of Hawaiʻi by the British.

|

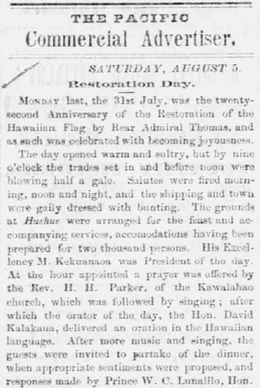

An article from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Aug. 5, 1865, describing the Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea celebration in Honolulu at which Lunalilo gave his speech.

An article from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Aug. 5, 1865, describing the Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea celebration in Honolulu at which Lunalilo gave his speech.

In a speech delivered before ʻŌiwi royalty and foreign dignitaries alike on July 31, 1865, William Charles Lunalilo described the scene of that five-month occupation. “Dark and gloomy indeed were those days,” Lunalilo remembered, “how the nation mourned during those few months of trial, thinking the government was gone perhaps forever in the hands of a foreign power. For five long lingering months, things remained as they then stood, until on the 31st day of July, the day we are now commemorating, we saw the flag that ‘had braved a thousand years the battle and the breeze,’ lowered by the hand of one of England’s sons” (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Aug. 5, 1865). That “son of England” was Admiral Richard Thomas, who, after hearing of Paulet’s criminal act, immediately sailed for Honolulu. After his arrival, on July 31, 1843, at the place now called “Thomas Square” in Honolulu, Thomas alongside Kauikeaouli lowered the British colors and raised the Hae Hawaiʻi once again—returning the symbol of the Kingdom’s independence to its rightful place of prominance in the islands. With this pono act, “ke ea o ka ʻāina” was also returned to its rightful place, and as Kauikeaouli proclaimed at the celebrations to follow in Nuʻuanu that day, “Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono.”

From that day forth, July 31 was celebrated as “Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea” (Ea Restoration Day) in Hawaiʻi, becoming Hawaiʻi’s first national holiday. It was a day that was celebrated throughout the nineteenth century with great enthusiasm by citizens of the Hawaiian Kingdom—often in the form of large community gatherings featuring song and chant, formal speeches, games, competitions and races on both the land and sea, and large feasts. In an 1865 newspaper article, John D. Kamanowai of Kunawai, Oʻahu, described Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea as: “Ka la hoi i hoihoiia mai ai ka hanu ola o keia Aupuni; ka la no hoi a kakou i ike aku ai i ka haule malie ana iho o ke Kalaunu o Beritania. O ka la keia a kakou i ku ai iluna a hooho ae ai i na leo me ka lanakila, ‘E Ola ka Moi i ke Akua. E Ola o Hawaii nei i ke Akua. Ua mau ke Ea o ka aina i ka pono.’ O keia ka la makahiki hou o ke kakou mau Mokupuni mai Hawaii a Niihau” (Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, July 29, 1865). (The day that the breath of life was returned to this Nation; the day that we all witnessed the graceful fall of the British Crown. This is the day that we stand up and call out with our voices in victory, “Life unto the Mōʻī from the Akua. Life unto Hawaiʻi from the Akua. The Ea of the ʻāina continues on in pono.” This is the new year’s day of our Islands from Hawaiʻi to Niʻihau.)

From that day forth, July 31 was celebrated as “Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea” (Ea Restoration Day) in Hawaiʻi, becoming Hawaiʻi’s first national holiday. It was a day that was celebrated throughout the nineteenth century with great enthusiasm by citizens of the Hawaiian Kingdom—often in the form of large community gatherings featuring song and chant, formal speeches, games, competitions and races on both the land and sea, and large feasts. In an 1865 newspaper article, John D. Kamanowai of Kunawai, Oʻahu, described Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea as: “Ka la hoi i hoihoiia mai ai ka hanu ola o keia Aupuni; ka la no hoi a kakou i ike aku ai i ka haule malie ana iho o ke Kalaunu o Beritania. O ka la keia a kakou i ku ai iluna a hooho ae ai i na leo me ka lanakila, ‘E Ola ka Moi i ke Akua. E Ola o Hawaii nei i ke Akua. Ua mau ke Ea o ka aina i ka pono.’ O keia ka la makahiki hou o ke kakou mau Mokupuni mai Hawaii a Niihau” (Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, July 29, 1865). (The day that the breath of life was returned to this Nation; the day that we all witnessed the graceful fall of the British Crown. This is the day that we stand up and call out with our voices in victory, “Life unto the Mōʻī from the Akua. Life unto Hawaiʻi from the Akua. The Ea of the ʻāina continues on in pono.” This is the new year’s day of our Islands from Hawaiʻi to Niʻihau.)

|

It should come as no surprise, however, that many of us today grew up never hearing of this great day of celebration. Like other national holidays of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea was not acknowledged by the governments that have occupied our homelands since the overthrow of our beloved Queen in 1893. It was not until last year that the County of Hawaiʻi first officially recognized Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea as a holiday, thanks to the efforts of a number of Hawaiʻi’s poʻe aloha ʻāina. Regardless, however, of whether or not the government recognizes this significant day in our history, it is nonetheless a kuleana of ours to honor Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea and celebrate all that it represents for the future of our lāhui Hawaiʻi, just as our kūpuna did.

In his stirring speech about the meanings of ea at a Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea gathering in Mānoa, Oʻahu, in 1871, Davida K. Kahalemaile called upon all of us, the people of this ʻāina, to remember this day for the many generations to come. “Auhea oukou,” Kahalemaile called out, “e na makua mea keiki i loaa ka pulapula, i puka i ke ao, ulu i ke ao, kawowo i ke ao...a hiki i ka hopena o kou kanikoo ana, hai aku oe i kau pulapula, ke noho la i ke ao malamalama, e hoomanao oe i ka la i hoihoiia mai ai ke ‘Ea o ke Aupuni,’ ke ola o ko Hawaii Pae Aina, ina no aole malama na Poo Aupuni, malama no kakou, o ko kakou malama ana, o ko ke alii malama ana no ia. Nolaila, e olioli kakou, a e hauoli pu me ka manao lokahi. E ola Ka Moi i ke Akua!!! Ua mau ke Ea o ka Aina i ka Pono!!!!” (Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, Aug. 12, 1871). (To all of you who are parents with children—those of you who have offspring that have emerged into this world, grown in the light, and multiplied in the light...Until the end of your days of walking with a cane, tell your offspring, ‘for as long as you live in the light of day, you should remember the day on which was returned the ‘Ea of the Nation,’ the life of all who live in these Hawaiian Islands.’ And if the Heads of the Government do not observe this day, we shall care for it. For our care and respect is indeed equal to that of the aliʻi. Therefore, let us celebrate and rejoice in unified thought. Life unto the Mōʻī from the Akua!!! Ua mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono!!!!). It is in this re-membering of our past that we breath Ea into our future. |

|

Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea Hāmākua, 2020

Our intention is not only to celebrate this important national holiday and its link to our history of a sustainable, independent past, but more importantly, we want this to become a day for us to gather annually as a community to share, learn, and envision the ways in which we can create sustainable, interdependent, thriving futures for our ʻāina and people here in Hāmākua.

For more information, follow Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili on Facebook & Instagram!

For more information, follow Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili on Facebook & Instagram!